Some historians have classified the Mexican-American War as a rehearsal for the Civil War, which would erupt approximately 15 years later.

Some historians have classified the Mexican-American War as a rehearsal for the Civil War, which would erupt approximately 15 years later.

Leading up to President James Polk’s May 13, 1846 announcement of the Mexican-American War, tension arose between President Polk and the Secretary of State, James Buchanan.

Following President James Polk’s announcement of war with Mexico, and Congress’ declaration of war, those in the Whig Party and those around the country had significantly different views of the war.

On the evening of April 24, 1846, Captain Seth Thornton and 68 American dragoons “went to confirm intelligence that a Mexican military force had crossed the Rio Grande” just miles away from where Brigadier General Zachary Taylor was camped. Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: Transformation of America, 1815-1848, 731.

Following the Democrats’ victory in the Election of 1844, President James Polk began negotiating with the British about the Oregon territory, which America had permitted Britain to occupy for several decades. See Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: Transformation of America, 1815-1848, 715.

“Philanthrop” to the Public

American Mercury (Hartford), November 19, 1787

Following are excerpts from an article in the American Mercury, located in Hartford, Connecticut:

“Let us for a moment call to view the most specious reason that can be urged by the advocates for anarchy and confusion, and the opposers to this glorious Constitution, and see what weight a rational man could give (more…)

James Polk, after winning the Election of 1844, set an agenda for what he hoped to accomplish during his presidency. Rather than elaborate on this agenda during his inaugural address, President Polk instead remained secretive. See Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: Transformation of America, 1815-1848, 708.

The Whigs had their own approach to interpreting manifest destiny, and that approach mainly applied to shaping America’s foreign policy.

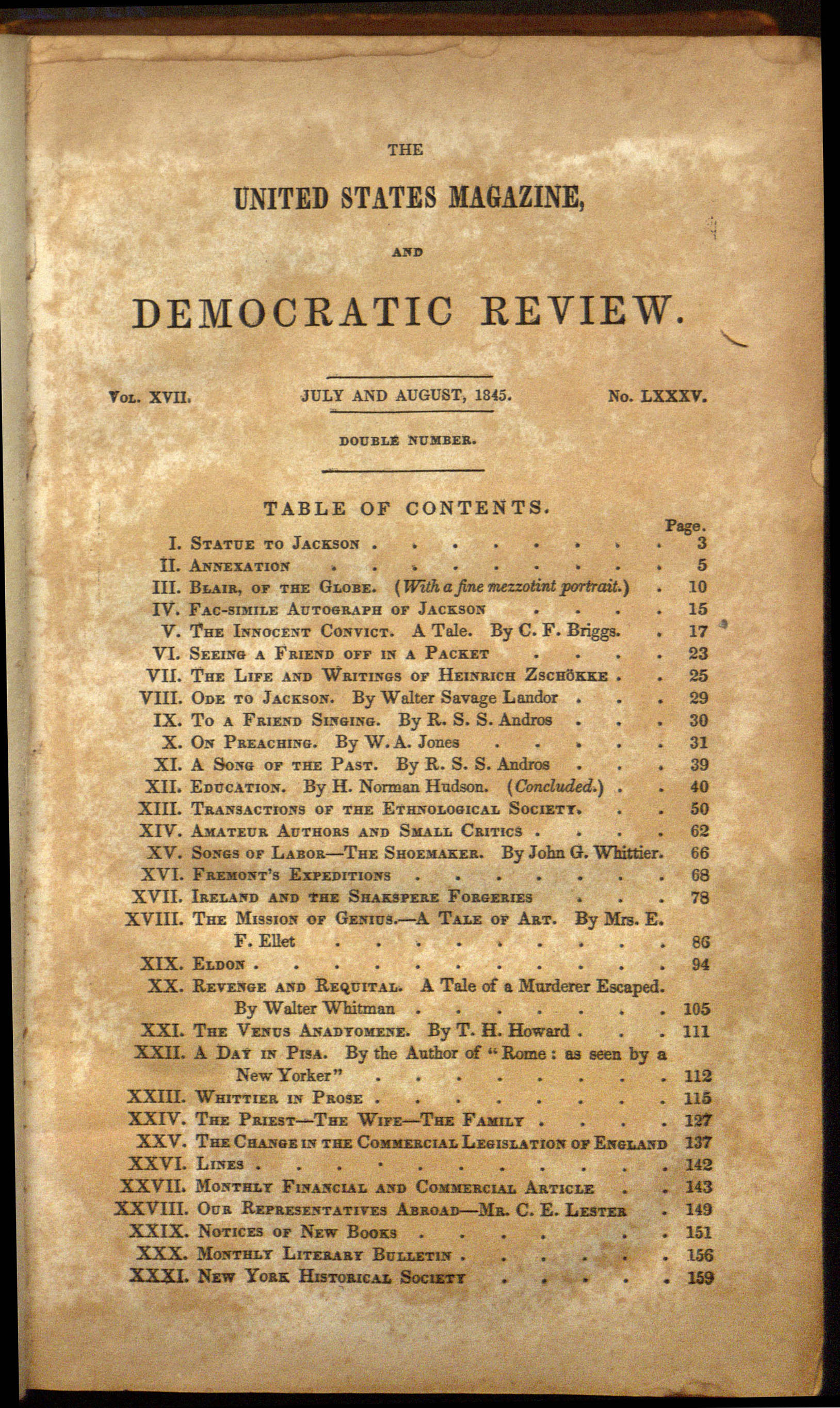

While many Americans would come to embrace manifest destiny, the idea that America would achieve its imperial destiny and dominate the continent, it was not a politician or president who coined the term. Rather, it was coined in 1845 in New York’s Democratic Review magazine. See Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: Transformation of America, 1815-1848, 702-03.