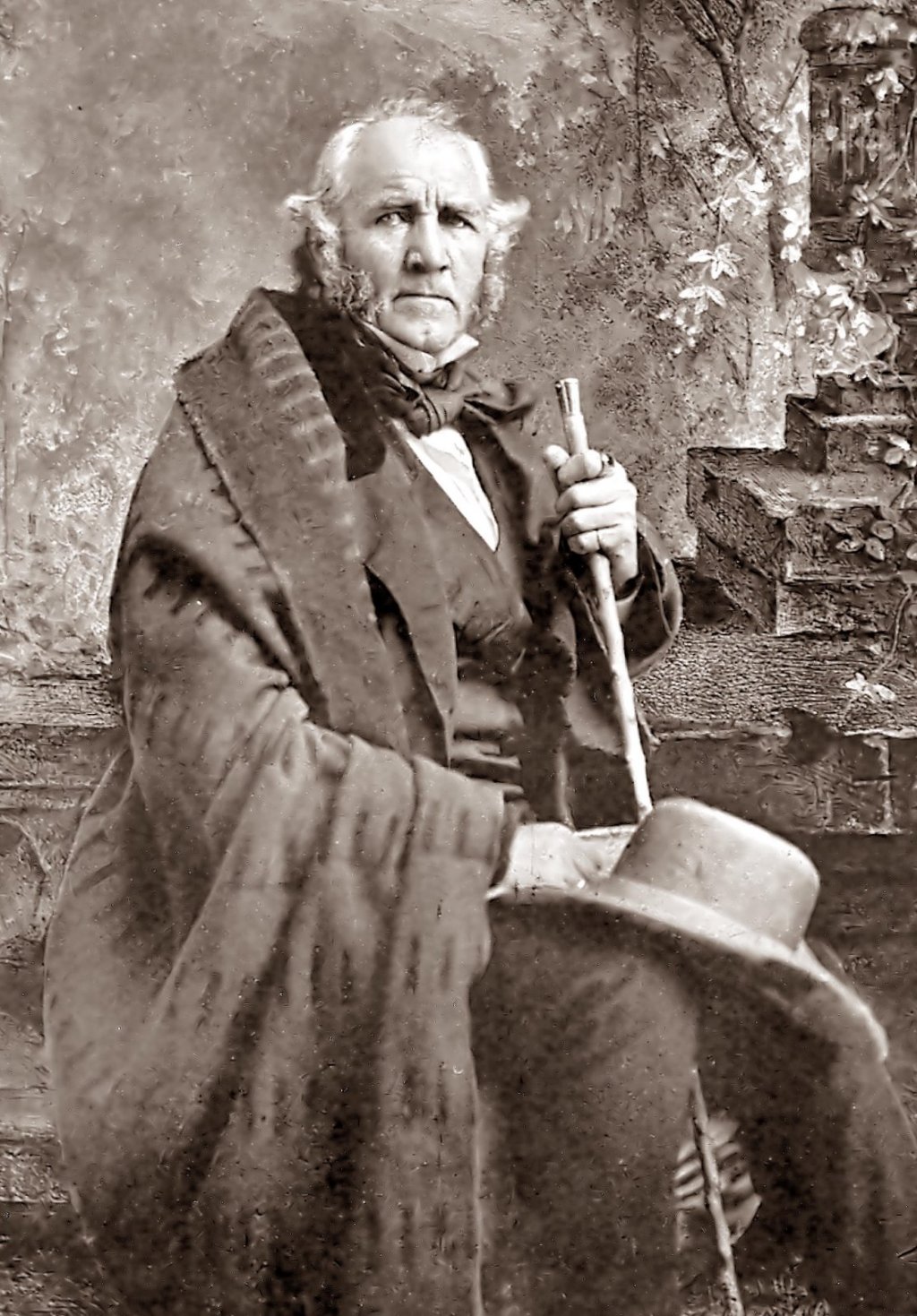

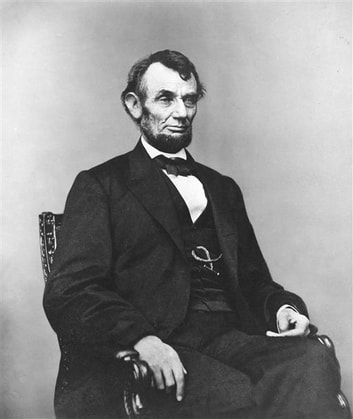

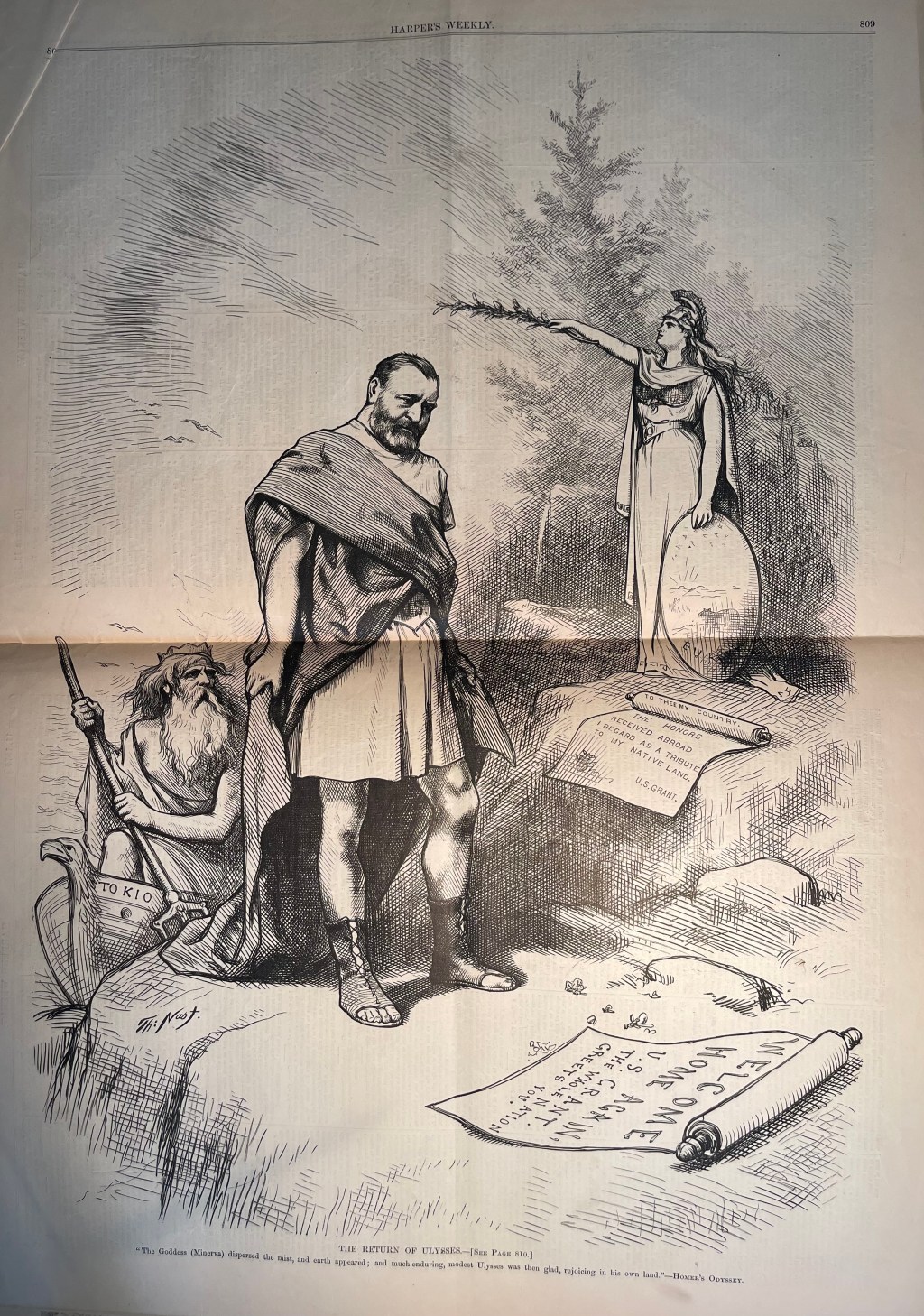

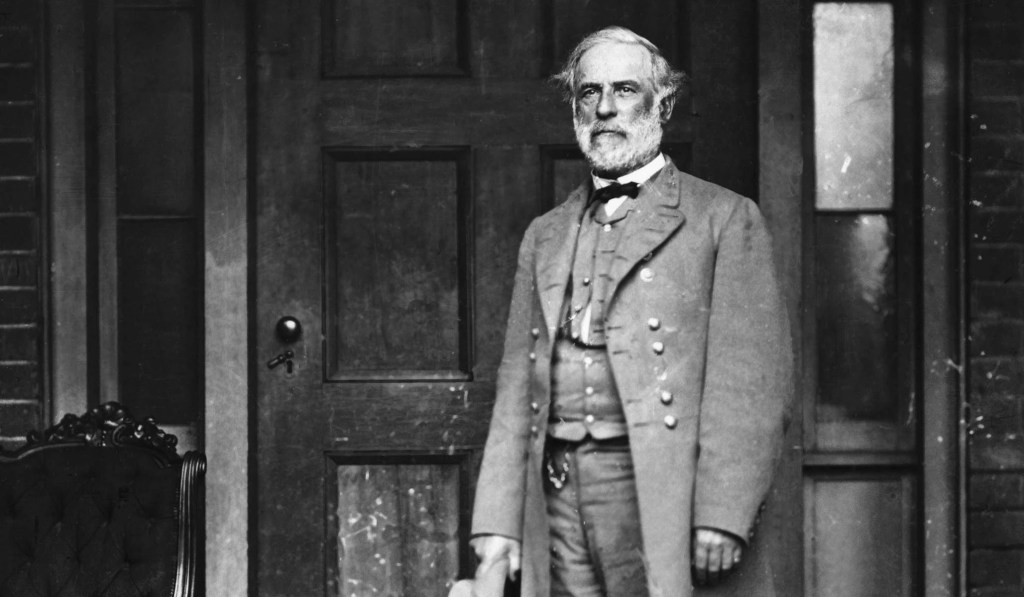

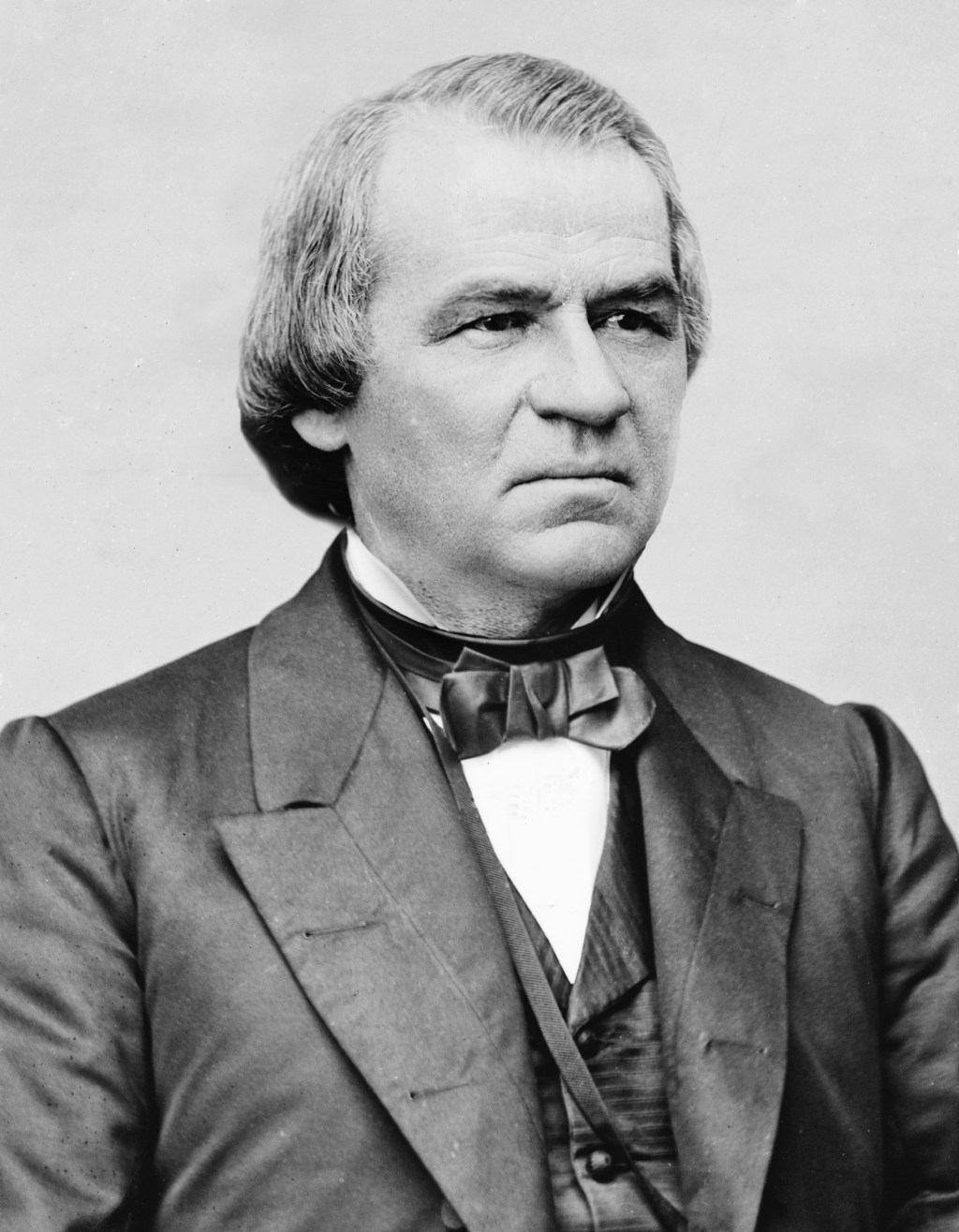

The Democratic Party was in turmoil. Its candidates were not winning, and many of its ideas had fallen out of favor. It was a long way from the days of the Party’s founding: Andrew Jackson and his disciple, Martin Van Buren, held power for the twelve years spanning 1829 to 1841 and—into the 1840s and 1850s—James Polk, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan continued to lead the Party into the White House albeit against candidates from the newly-formed and then soon-to-be-disbanded Whig Party. Then, following the emergence of the Republican Party—an emergence which culminated in its candidate, Abraham Lincoln, prevailing in the elections of 1860 and 1864—Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President and then successor as President, oversaw a one-term presidency which came to an end in 1869. Johnson, partly because he was serving between two titans of the century (Lincoln and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant), was always going to struggle to earn admiration but, unlike Lincoln and Grant, Johnson was technically a Democrat, and perhaps because he was so thoroughly shamed for his actions as President, the Party would scarcely recognize him as a member. Whether a result of Johnson’s malfeasance or not, following Johnson’s presidency came an era of Republican dominance: Republican Grant won two consecutive terms, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes secured a succeeding term, Republican James Garfield then was victorious, and following his assassination, Republican Chester Arthur served out the remainder of that term. That brought the parties and the country to 1884. As the election of 1884 approached, it had been decades since a strong, effective Democrat—a Democrat who embodied the Party’s principles and would be a standard bearer for the Party, unlike the postbellum Democratic President, Johnson, or the last antebellum one, Buchanan—held office, and for Democrats to win this election, it would take someone special; someone who would be transformative even if only in a way that was possible at the time. As fortune would have it, it could not be a wartime presidency or a presidency that birthed fundamental change in American government, but that was because the circumstances of the era did not call for such a President; it could, however, be a presidency that tackled one of the biggest issues of the time: corruption.

(more…)