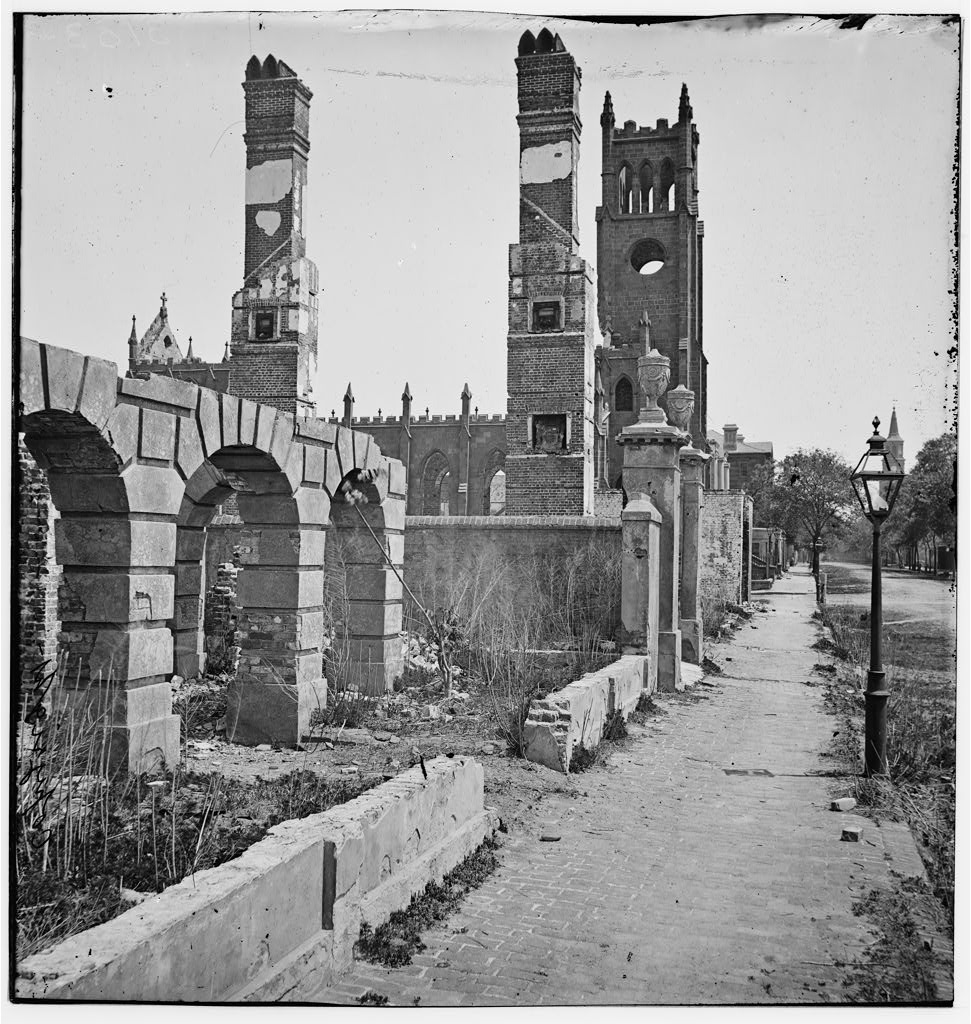

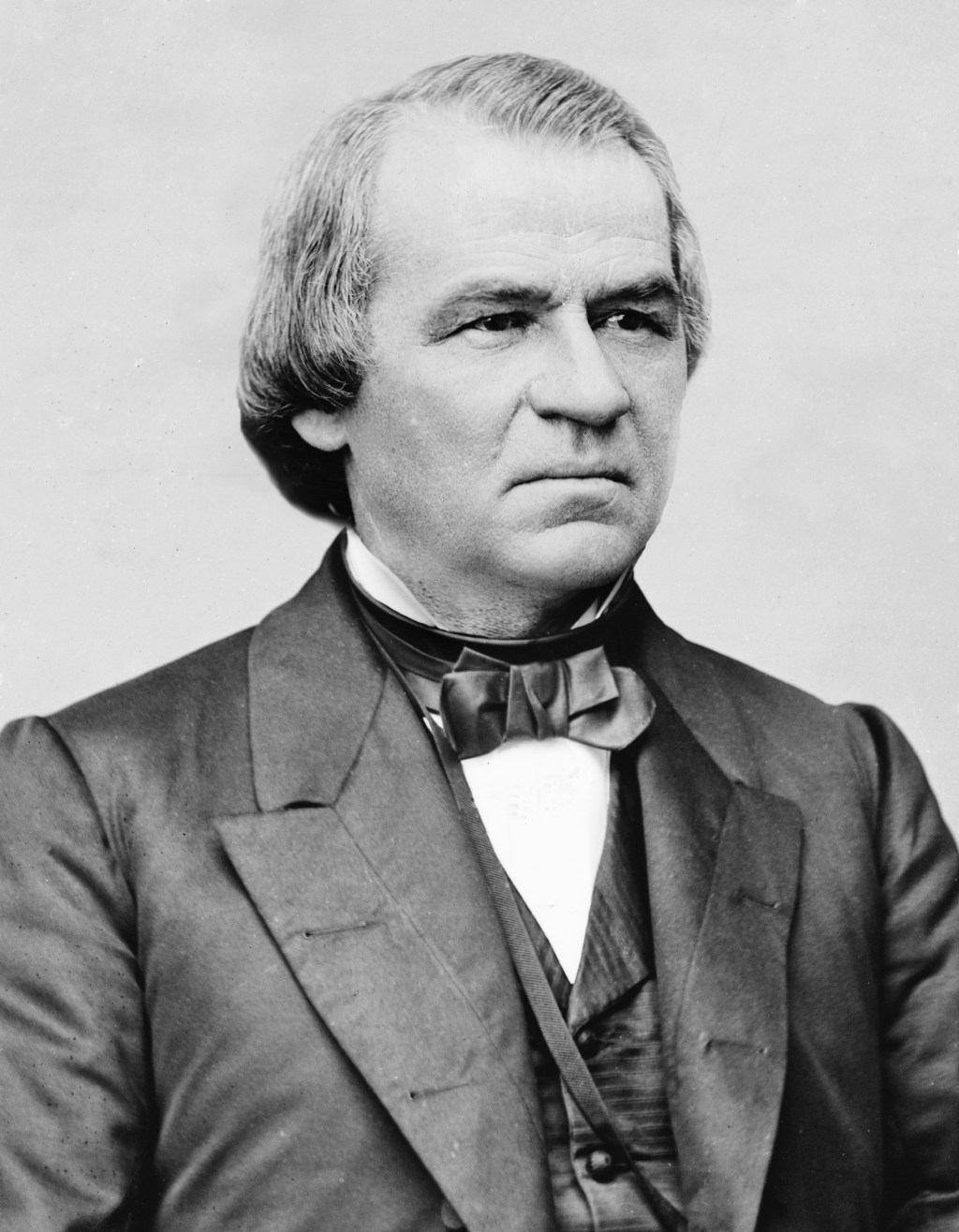

The years after the Civil War, until 1877, were replete with novel uncertainties. The country had changed: the qualities that defined antebellum America had vanished; those who had been the most vocal before the war—soon-to-be Confederates—had seen their soapbox taken by the “Radical Republicans,” Republicans who sought to not only end slavery but to bring into effect equality amongst the races. Regardless of political party or geographic location, the country and its citizens had the task of reconstructing the United States, every one of them, and that task began before the Civil War’s end. President Abraham Lincoln spoke of his hope to reconcile the “disorganized and discordant elements” of the country, and he said: “I presented a plan of re-construction (as the phrase goes) which, I promised, if adopted by any State, should be acceptable to, and sustained by, the Executive government of the nation. I distinctly stated that this was not the only plan which might possibly be acceptable.”[i] Lincoln died four days later without fully setting forth his vision for how the nation may reconstruct itself, but events would soon render that vision—broad and ambiguous as it was—antiquated: soon after his death, the same federal government that had grown to enjoy extraordinary power (such as suspending the writ of habeas corpus) would go from having an authentic political genius, Lincoln, at its helm to having Andrew Johnson, a disagreeable at best (belligerent at worst) as executive; and not so long after Johnson took power, roving bands of the Ku Klux Klan acted in concert with state officials throughout the South to subjugate—by any means—those who had been freed.

(more…)