During the Gilded Age, millions of Americans saw their work lives transform: no longer would it be so common for the working man or woman to survive based on what he or she produced; rather, that worker would receive payment—from an employer or a contractor—for the time worked. That change allowed for the possibility during the Gilded Age for the older generation to reflect on their younger years, before the Civil War, and how they had sold most of what they had grown or made (and how they had then needed a wide variety of skills to not only grow or make those goods but to bring those goods to market and actually sell them). During the Gilded Age, that same generation could have been working the last years of their working lives reporting to a factory for work; work that likely had a significant element of danger and that may have required them to use a fraction of the skills that had served as their saving grace during their younger years. For the generations of Americans that have come after the Gilded Age, the system of wage labor has been no oddity. It became a substantial part of the modern way of life and not only in America. What would have struck and should strike subsequent generations, however, were the mechanics of the American economy in which wage labor was born and how the wage labor system in its rawest form did not extend even some of the most basic protections to workers.

(more…)Tag: Economic Development

-

America in 1870

Although America, by 1870, was still not one hundred years into its life as a country, it had the blessings and curses of an industrialized nation—some inherited from the British but others uniquely American.[i] Among the blessings was widespread prosperity: the United States then had “74 percent of British and 128 percent of German per-capita income.”[ii] Although many Europeans had come to see America as a country filled with “little more than amiable backwoods-men not yet ready for unsupervised outings on the world stage,” those Europeans had erred in reaching that conclusion as was evident at the London Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851 when Americans showed their latest inventions in their “outpost of wizardry and wonder” with machines that “did things that the world earnestly wished machines to do—stamp out nails, cut stone, mold candles—but with a neatness, dispatch, and tireless reliability that left other nations blinking.”[iii] But that presentation of the United States to the world lacked the nuance that was evident to those who toured the country; prosperity may have been widespread, but it was not equally distributed and it was not without hardship.

(more…) -

The Obstinacy of the North and South

Construction on the Capitol in 1859. Courtesy: William England, Getty Images. By 1859, the northern and southern sections of America had developed different economic systems, cultural norms, and approaches to permitting slavery. Congress and the political parties had been able to overlook those differences for the sake of self-preservation and advancement of the collective agenda. As 1859 concluded and 1860 sprang, Americans understood that the status quo of compromise was not to continue much longer. (more…)

-

The Evolving Political Parties of the 1850s

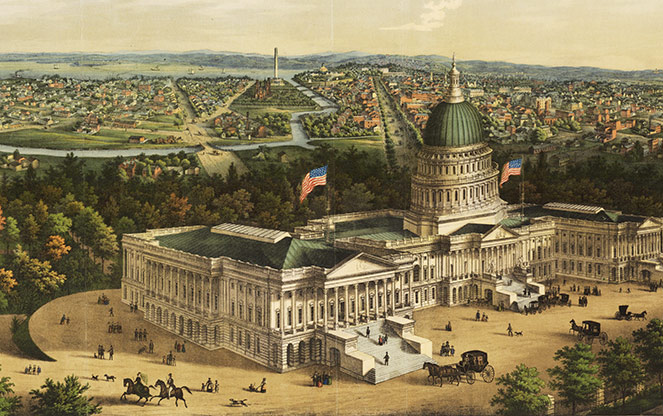

Panoramic View of Washington, DC in 1856. Courtesy: E. Sachse & Co. The Democratic Party and Whig Party were the dominant political parties from the early 1830s up until the mid-1850s. Both were institutions in national politics despite not having a coherent national organization by cobbling together a diverse group of states to win elections. While the Democrats had a more populist agenda, the Whigs were more focused on pursuing industrialization and development of the country. See David Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861, 226. While the Democratic Party would survive to the present day, the Whig Party would not survive the mid-1850s, not as a result of its own ineptness but because of the changing political landscape of that era. (more…)

-

The Work Divide

Painting of Cincinnati, Ohio from Newport, Kentucky. By: John Caspar Wild. The North and the South had come to develop two distinct cultures by the mid-1800s. One of those fundamental differences was the nature of work.

-

The Country of the Future

Home in the Woods. By: Thomas Cole. By 1848, America had undergone a significant transformation from the America that the Founding Fathers left just a few decades before.

-

Election of 1848: Whig Victory

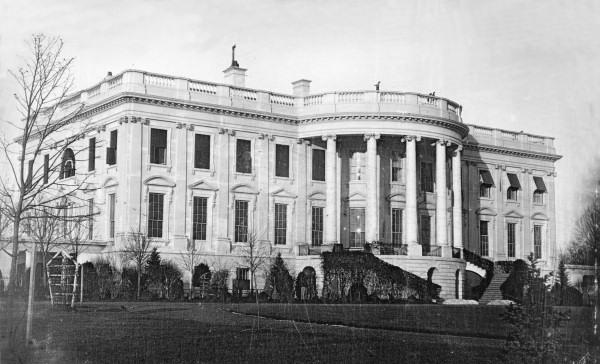

The White House in 1848. Credit: Library of Congress. On November 7, 1848, Americans went to the polls to choose between Martin Van Buren, Zachary Taylor, and Lewis Cass.

-

The Whigs’ Manifest Destiny

William Ellery Channing. By: Henry Cheever Pratt. The Whigs had their own approach to interpreting manifest destiny, and that approach mainly applied to shaping America’s foreign policy.

-

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842

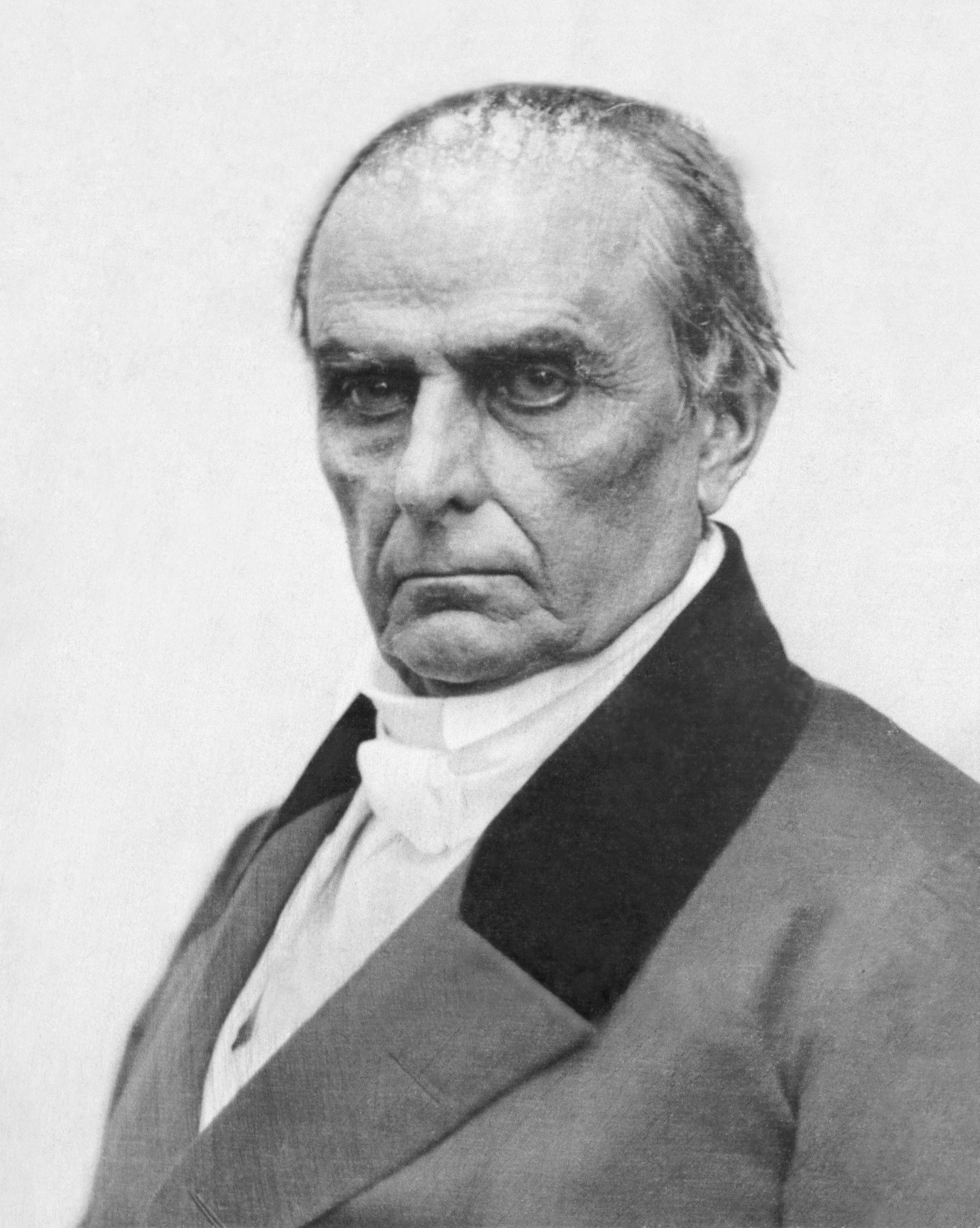

Daniel Webster. Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State under President John Tyler, brought a breadth of experience and dignity to the office, but he also brought “a different perspective on Anglo-American relations.” Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: Transformation of America, 1815-1848, 672.

-

The Emergence of Bankruptcy

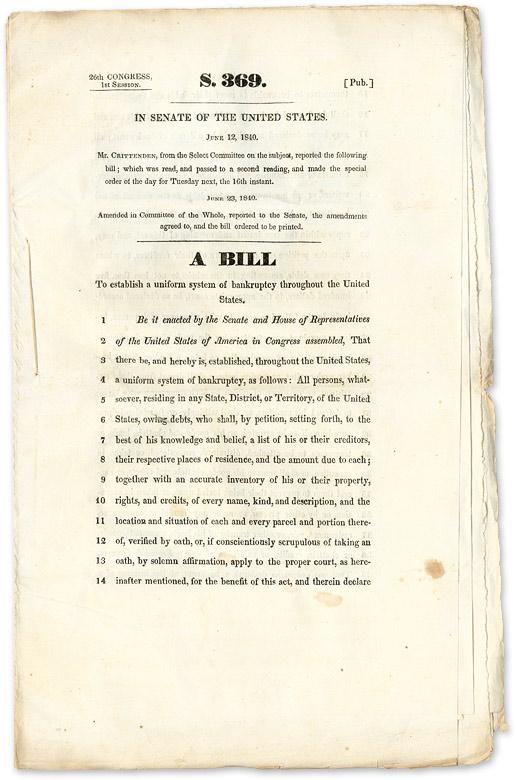

The Bankruptcy Act of 1841. In the wake of the Panics of 1837 and 1839, Congress sent the White House a new bill to be signed into law: The Bankruptcy Act of 1841. See Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: Transformation of America, 1815-1848, 593. From then on, bankruptcy would be part of American life, providing an option for when debts become overwhelming.