March 21, 1861

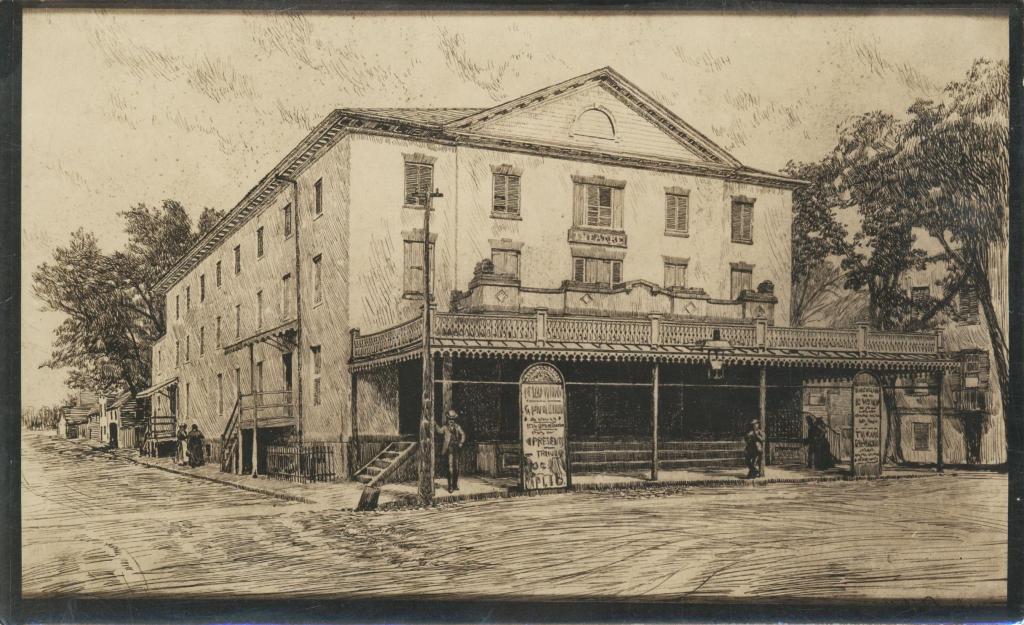

In Savannah, Georgia, at its Atheneum—a theater for shows and oratory—the vice-president of the Confederacy, Alexander H. Stephens, came to speak about the events leading up to states seceding from the Union and forming the Confederacy. The pace of these events had been swift and sure to cause consternation with questions abound as to what would happen next. To hear Stephens speak that day was to gain a better grasp of what was to come and perhaps a sense of comfort that all would be well.

(more…)