January 8, 1861

A few weeks after Henry Adams wrote to his brother Charles Francis Adams Jr. about the scenes playing out post-election in Washington, D.C., he wrote again—this time about the potential for warfare to soon begin.

(more…)January 8, 1861

A few weeks after Henry Adams wrote to his brother Charles Francis Adams Jr. about the scenes playing out post-election in Washington, D.C., he wrote again—this time about the potential for warfare to soon begin.

(more…)Independent Journal (New York)

January 19, 1788

Engineering a coup can be difficult. Usually, it requires a military to not only lose faith in the civilian government but to organize an overthrowing of that government. Democratic republics fear this prospect as much as any other type of government. Although democratic republics are better suited for allowing their citizens to vent their anger—through the vote, protest, and other expressions of speech—and presumably have a healthier, happier citizenry as a result, the threat still lingers. And during any period of American history, the potential for a standing army—one of permanence and at times one of substantial size—has raised the specter of a military coup on top of the obvious dedication of resources needed to support a standing army.

(more…)January 16, 1788

A government must provide its people—all of its people, varied as they are—with a structure that fosters self-preservation. In the South, for a long stretch of time, that sense of self-preservation was crucial. There was no denying that the slave economy was central to its existence that it was therefore always going to have tension with northern states. This was as true in 1788 as in 1861. And in 1788, there was rampant, raging debate surrounding the draft Constitution. In South Carolina’s legislature, two men—Rawlins Lowndes and Edward Rutledge—debated the merits of that draft, taking different sides on whether it warranted adoption.

(more…)Massachusetts Ratifying Convention

January 24, 1788

The Constitution empowers Congress to “raise and support Armies” with the limitation that any appropriation of money for raising and supporting armies must be limited to a two-year term (Article I, Section 8, Clause 12). At the Massachusetts Ratifying Convention, there was debate as to whether that authority should exist at all and whether it should be housed with Congress.

(more…)Massachusetts Ratifying Convention.

January 15, 1788

The duration of a term for a member of the House of Representatives was a contentious issue: while some favored one-year terms, others—such as Fisher Ames—advocated for two-year terms. To Ames, a member of the House would be unlikely to learn enough about the country in a year to cast informed votes and to represent the interests of the people. Adding to that was the fact that the country was set to grow: Ames expressed his hope that the country would be home to “fifty millions of happy people” and that a member of the House would require at “least two years in office” to enable that member “to judge of the trade and interests of states which he never saw.” But, also at issue was the expression and suppression of the will of the people through their representatives.

(more…)

Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention.

December 1, 1787

James Wilson, one of the most eloquent and artful of his time, spoke at Pennsylvania’s Ratifying Convention on December 1, 1787 about the merits of the draft Constitution. One of the crucial components of the draft was its creation of the legislature as a “restrained” legislature; a legislature that would “give permanency, stability and security” to the new government.

(more…)Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention.

November 30, 1787.

At the Pennsylvania Convention, Robert Whitehill rose to speak about the proposed Constitution including—and perhaps especially—its biggest flaw. To Whitehill, despite the fact that the country’s learned people devised the Constitution, “the defect is in the system itself,—there lies the evil which. no argument can palliate, no sophistry can disguise.” The Constitution, as it was written, “must eventually annihilate the independent sovereignty of the several states” given the power that the Constitution allotted to the federal government.

(more…)

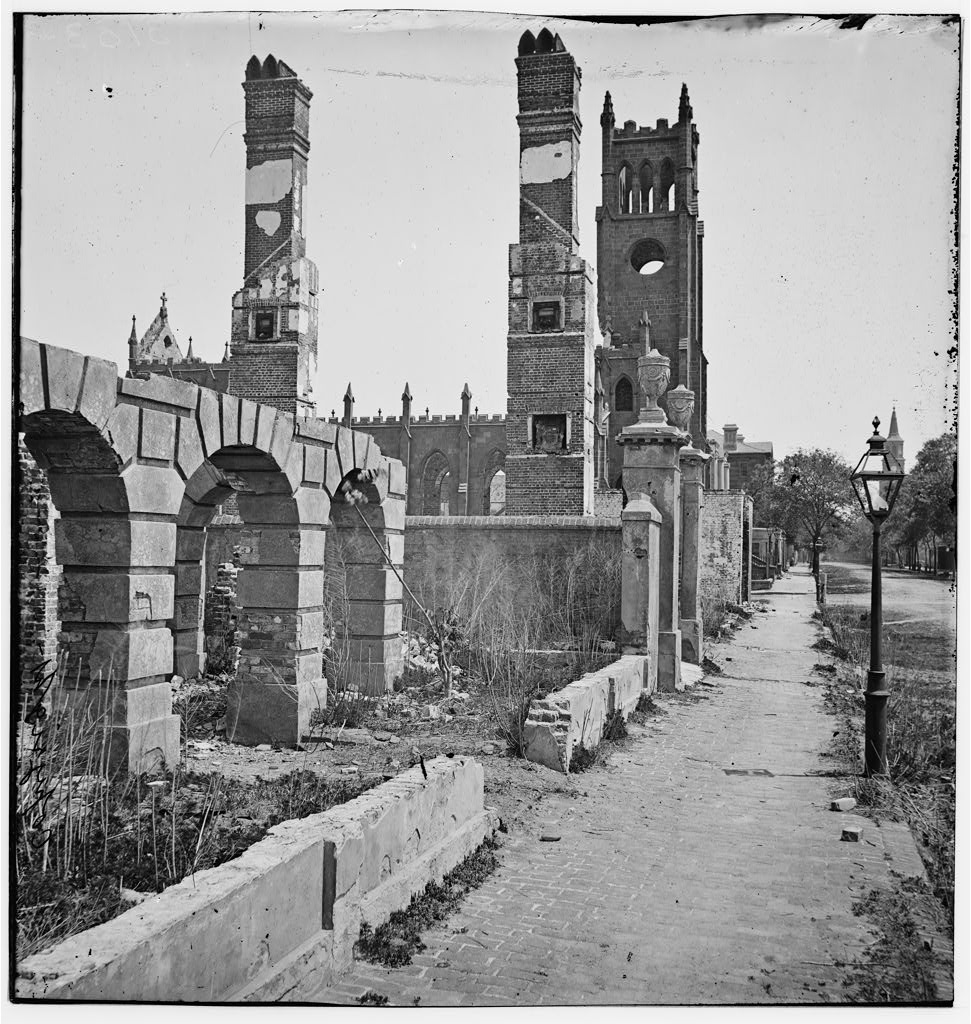

The years after the Civil War, until 1877, were replete with novel uncertainties. The country had changed: the qualities that defined antebellum America had vanished; those who had been the most vocal before the war—soon-to-be Confederates—had seen their soapbox taken by the “Radical Republicans,” Republicans who sought to not only end slavery but to bring into effect equality amongst the races. Regardless of political party or geographic location, the country and its citizens had the task of reconstructing the United States, every one of them, and that task began before the Civil War’s end. President Abraham Lincoln spoke of his hope to reconcile the “disorganized and discordant elements” of the country, and he said: “I presented a plan of re-construction (as the phrase goes) which, I promised, if adopted by any State, should be acceptable to, and sustained by, the Executive government of the nation. I distinctly stated that this was not the only plan which might possibly be acceptable.”[i] Lincoln died four days later without fully setting forth his vision for how the nation may reconstruct itself, but events would soon render that vision—broad and ambiguous as it was—antiquated: soon after his death, the same federal government that had grown to enjoy extraordinary power (such as suspending the writ of habeas corpus) would go from having an authentic political genius, Lincoln, at its helm to having Andrew Johnson, a disagreeable at best (belligerent at worst) as executive; and not so long after Johnson took power, roving bands of the Ku Klux Klan acted in concert with state officials throughout the South to subjugate—by any means—those who had been freed.

(more…)