It was a time of oratory and a time when Ohioans became President. James Garfield was a product of the time. He was born into “a poor family” and “an intellectual in love with books.”[i] He attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute as a student and janitor, and by the following year, he became an assistant professor.[ii] Garfield was a man who treasured intellect. When William Dean Howells came to Garfield’s home in Hiram, Ohio in 1870, he sat on the porch and told a story about New England’s poets; Garfield “stopped him, ran out into his yard, and hallooed the neighbors sitting on their porches: ‘He’s telling about Holmes, and Longfellow, and Lowell, and Whittier.’”[iii] At a time when the Midwest fostered “a strong tradition of vernacular intellectualism” that manifested itself in “crowds for the touring lectures, the lyceums, and later the Chautauquas,” the neighbors gathered and listened “to Howells while the whippoorwills flew and sang in the evening air.”[iv]

(more…)Tag: James Blaine

-

The Assassination of James Garfield

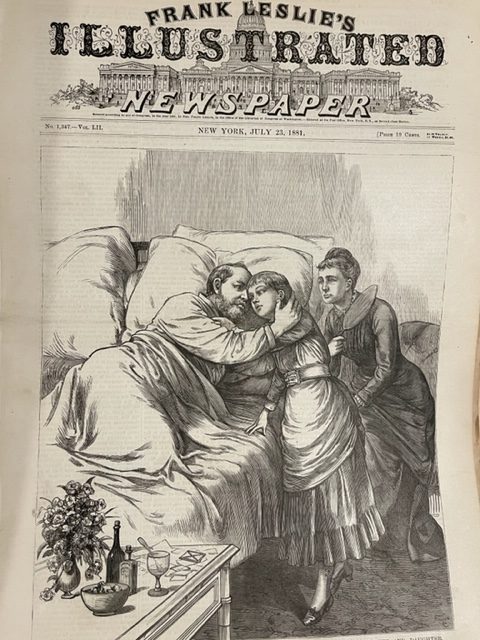

In the late afternoon, during the summer, a thunderstorm rolled its way through the nation’s capital. Although it first had the effect of cooling the thick Washington air, the effect was fleeting. By 10 o’clock that night, the President could have hope for relief: a new apparatus—rumored to be quite effective against the oppressively humid air of India—had arrived. Staff assembled V-shaped troughs, made of zinc and “filled with ice and water,” and placed them under the windows of the President’s room.[i] The water lessened the humidity, and the ice cooled the air entering the room through the windows.[ii] The President’s pulse, temperature, and respiration satisfied his physicians, and there was optimism that “the worst was over.”[iii] It had been several weeks since the attempted assassination, and the 20th President of the United States, James Garfield, was having his secretaries attend to the pressing matters of the country as he rested.[iv] His wife and children visited his bedside, and his daughter, Mollie, “nestled her fresh face in his beard,” keeping her composure just as her mother did.[v] The President “kissed her and stroked her hair, and then she took a seat near her mother” when the “boys came in presently with manful bearing and remained a few minutes.”[vi] The cooling apparatus, the doctors said, was not giving “entire satisfaction,” and a new device—one that was “similar to that used in the mines to cool the air and send it into the chamber through the registers”—was set to be installed to relieve the President from his symptoms.[vii]

(more…) -

The Election of 1884

The Democratic Party was in turmoil. Its candidates were not winning, and many of its ideas had fallen out of favor. It was a long way from the days of the Party’s founding: Andrew Jackson and his disciple, Martin Van Buren, held power for the twelve years spanning 1829 to 1841 and—into the 1840s and 1850s—James Polk, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan continued to lead the Party into the White House albeit against candidates from the newly-formed and then soon-to-be-disbanded Whig Party. Then, following the emergence of the Republican Party—an emergence which culminated in its candidate, Abraham Lincoln, prevailing in the elections of 1860 and 1864—Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President and then successor as President, oversaw a one-term presidency which came to an end in 1869. Johnson, partly because he was serving between two titans of the century (Lincoln and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant), was always going to struggle to earn admiration but, unlike Lincoln and Grant, Johnson was technically a Democrat, and perhaps because he was so thoroughly shamed for his actions as President, the Party would scarcely recognize him as a member. Whether a result of Johnson’s malfeasance or not, following Johnson’s presidency came an era of Republican dominance: Republican Grant won two consecutive terms, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes secured a succeeding term, Republican James Garfield then was victorious, and following his assassination, Republican Chester Arthur served out the remainder of that term. That brought the parties and the country to 1884. As the election of 1884 approached, it had been decades since a strong, effective Democrat—a Democrat who embodied the Party’s principles and would be a standard bearer for the Party, unlike the postbellum Democratic President, Johnson, or the last antebellum one, Buchanan—held office, and for Democrats to win this election, it would take someone special; someone who would be transformative even if only in a way that was possible at the time. As fortune would have it, it could not be a wartime presidency or a presidency that birthed fundamental change in American government, but that was because the circumstances of the era did not call for such a President; it could, however, be a presidency that tackled one of the biggest issues of the time: corruption.

(more…) -

The Election of 1876

In celebrating America’s first centennial, on July 4, 1876, one must have recalled the tumult of that century: a war to secure independence, a second war to defend newly-obtained independence, and then a civil war the consequences of which the country was still grappling with eleven years after its end. But there also had been extraordinary success in that century, albeit not without cost; by the 100-year mark, the country had shown itself and the world that its Constitution—that centerpiece of democracy—was holding strong (with 18 Presidents, 44 Congresses, and 43 Supreme Court justices already having served their government by that time), and the country had expanded several times over in geographic size, putting it in command of a wealth of resources as its cities, industries, and agriculture prospered. Several months after the centennial celebration was the next presidential election, and during the life of the country, while most elections had gone smoothly, some had not—the elections of 1800 and 1824 were resolved by the House of Representatives choosing the victor as no candidate secured a majority of Electoral College votes and the election of 1860 was soon followed by the secession of Southern states. And yet, even with those anomalous elections in view, the upcoming election of 1876 was to become one unlike any other in American history.

(more…) -

Crédit Mobilier

Americans’ trust in their government has always ebbed and flowed, and those ebbs and flows have largely depended on whether the government and its officers have acted in ways that earned the trust of its citizens or in ways that led the government to be mired in scandal—therefore sullying its reputation. Some of the largest ebbs in trust have come after officials in the top echelon of government—Senators, Representatives, Presidents and their cabinets—have used their offices for their own benefit. Two months before the election of 1872, news broke of a scandal that would extend well into 1873 and implicate politicians as prominent as the Vice President, and that scandal foreshadowed the ways in which big business and politics would intertwine in not only the Nineteenth Century but the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries.

(more…)