The Democratic Party was in turmoil. Its candidates were not winning, and many of its ideas had fallen out of favor. It was a long way from the days of the Party’s founding: Andrew Jackson and his disciple, Martin Van Buren, held power for the twelve years spanning 1829 to 1841 and—into the 1840s and 1850s—James Polk, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan continued to lead the Party into the White House albeit against candidates from the newly-formed and then soon-to-be-disbanded Whig Party. Then, following the emergence of the Republican Party—an emergence which culminated in its candidate, Abraham Lincoln, prevailing in the elections of 1860 and 1864—Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President and then successor as President, oversaw a one-term presidency which came to an end in 1869. Johnson, partly because he was serving between two titans of the century (Lincoln and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant), was always going to struggle to earn admiration but, unlike Lincoln and Grant, Johnson was technically a Democrat, and perhaps because he was so thoroughly shamed for his actions as President, the Party would scarcely recognize him as a member. Whether a result of Johnson’s malfeasance or not, following Johnson’s presidency came an era of Republican dominance: Republican Grant won two consecutive terms, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes secured a succeeding term, Republican James Garfield then was victorious, and following his assassination, Republican Chester Arthur served out the remainder of that term. That brought the parties and the country to 1884. As the election of 1884 approached, it had been decades since a strong, effective Democrat—a Democrat who embodied the Party’s principles and would be a standard bearer for the Party, unlike the postbellum Democratic President, Johnson, or the last antebellum one, Buchanan—held office, and for Democrats to win this election, it would take someone special; someone who would be transformative even if only in a way that was possible at the time. As fortune would have it, it could not be a wartime presidency or a presidency that birthed fundamental change in American government, but that was because the circumstances of the era did not call for such a President; it could, however, be a presidency that tackled one of the biggest issues of the time: corruption.

(more…)Tag: James Polk

-

The Election of 1860

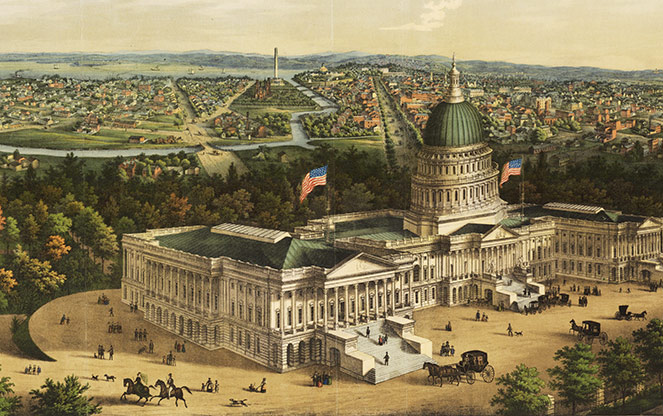

The United States Capitol in 1860. Courtesy: Library of Congress Every presidential election is consequential, but the Election of 1860 would play a significant role in whether the United States would remain one nation. The division of the North and South on the issue of slavery threatened to cause a secession of the South. The result of the election would determine whether that threat would materialize and cause a Second American Revolution. (more…)

-

The Evolving Political Parties of the 1850s

Panoramic View of Washington, DC in 1856. Courtesy: E. Sachse & Co. The Democratic Party and Whig Party were the dominant political parties from the early 1830s up until the mid-1850s. Both were institutions in national politics despite not having a coherent national organization by cobbling together a diverse group of states to win elections. While the Democrats had a more populist agenda, the Whigs were more focused on pursuing industrialization and development of the country. See David Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861, 226. While the Democratic Party would survive to the present day, the Whig Party would not survive the mid-1850s, not as a result of its own ineptness but because of the changing political landscape of that era. (more…)

-

Halting Manifest Destiny

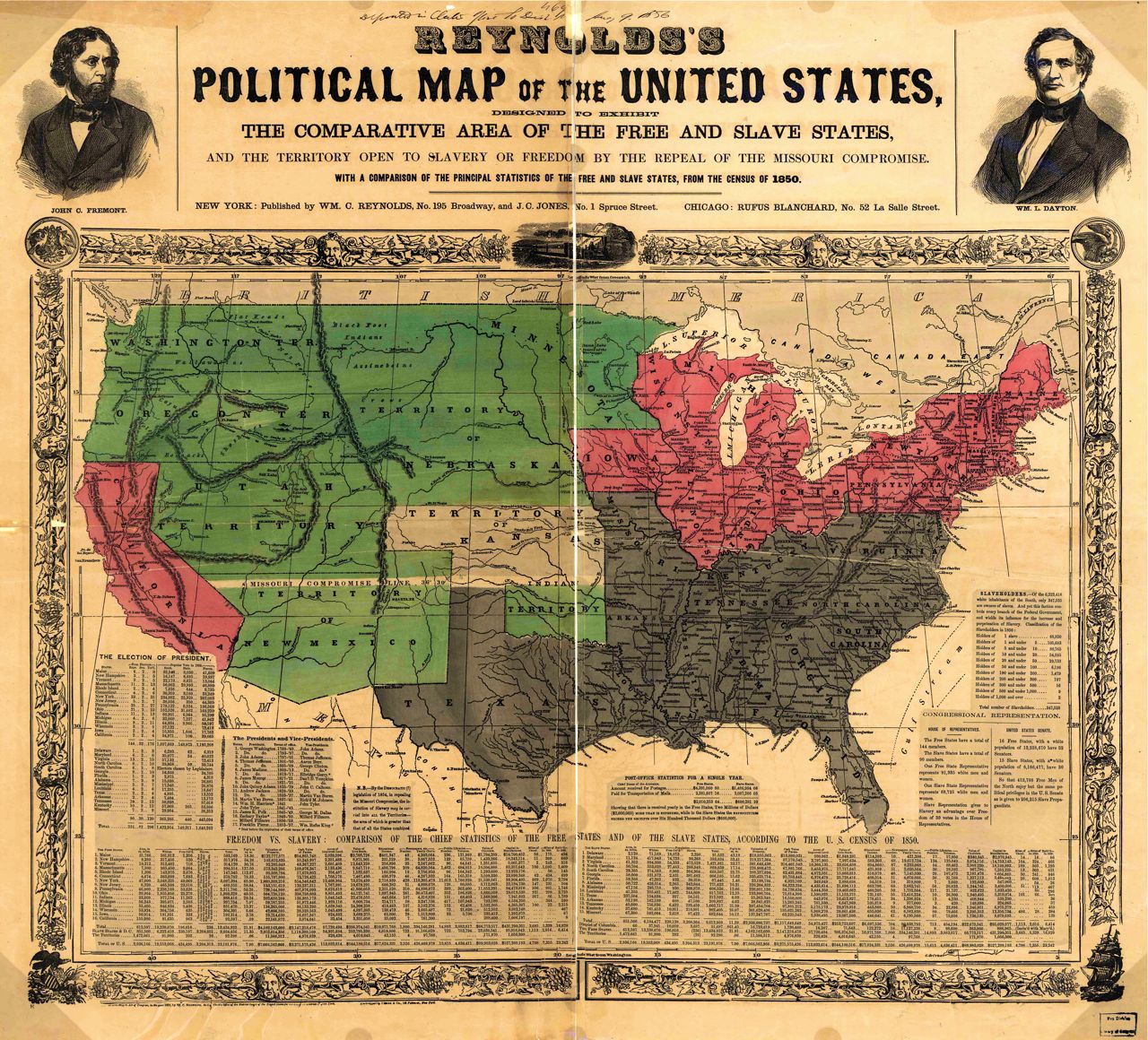

Map of America in 1850. During 1854, while the Kansas-Nebraska Act was making its way through Congress and to President Franklin Pierce’s desk, there were significant developments throughout the country that would have lessen the manifest destiny fever that had captured the nation’s attention up to that point. One of the hallmarks of American progress was nearing its end. (more…)

-

The Election of 1852

President Franklin Pierce. By: George P.A. Healy. With the first term of Millard Fillmore’s presidency winding down in 1852, the Democrats felt a sense of momentum that they could reclaim the White House. In the midterm elections of 1850, the Democrats secured 140 of the 233 seats in the House of Representatives, eclipsing the Whig Party. See David Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861, 141.

-

A Deadlocked and Destructive Congress

The United States Capitol in 1848. Unknown Photographer, credit Library of Congress. During President James Polk’s administration, Congress grappled with resolving sectional tension arising out of whether slavery would be extended to newly acquired land from Mexico as well as the Oregon territory. Congress did not resolve that sectional tension but exacerbated it in what may have been one of the most deadlocked and destructive Congresses in American history. (more…)

-

The Theories of Slavery

Trout Fishing in Sullivan County, New York. By: Henry Inman. In the 15 years leading up to the Civil War, a wide variety of theories emerged for how the federal government should deal with slavery expanding, or not expanding, into the territories acquired by the United States.

-

The American Spirit of the 1840s

The Van Rensselaer Manor House. By: Thomas Cole. Through the early 1800s and well into the 1840s, Americans had developed a sense of unity and pride about their country.

-

Election of 1848: The Candidates

The Whig Ticket for President, Zachary Taylor, and Vice President, Millard Fillmore. The Election of 1848 was bound to be unique, as President James Polk had made clear that he would serve only one term as president. With that, the Whigs and the Democrats had to put forth candidates that could meet the parties’ respective goals of reversing President Polk’s policies (the Whigs) and expanding on President Polk’s policies (the Democrats).