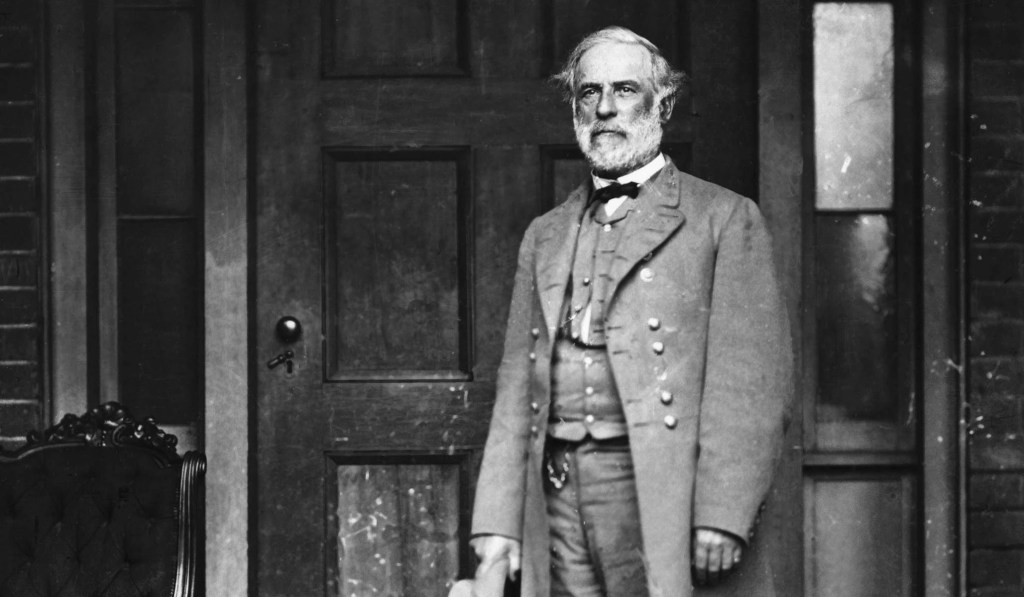

No figures in American history earn universal admiration. As years—and generations—pass, legacies change. As morals, priorities, and political issues evolve, so do understandings of those people in the past who brought change—good, bad, or otherwise—to the country. For some figures, like Abraham Lincoln, whose authentic genius is admired generation after generation, their merit is questioned only by those who unreasonably say the great should have been greater. For others, it becomes much more varied and nuanced, and for Robert E. Lee, his legacy has always differed depending on the part of the country where his legacy is measured and the tenor of the moment. This is because, perhaps more than even Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Lee became a symbol of the Confederacy—with all its ills but also its potential for what might have been.

(more…)Tag: Peninsula Campaign

-

The Battle of Cold Harbor

Within a dozen miles of Richmond sat the dusty crossroads of Cold Harbor. The town, with its tavern and “triangular grove of trees at the intersection of five roads,” would be the next stop in Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign in Virginia to defeat Robert E. Lee. There, approximately 109,000 Union troops sat ready to take on around 59,000 entrenched rebels.[i] The battle was likely to only be a continuation of the “relentless, ceaseless warfare” that had characterized Grant’s campaign into Virginia throughout 1864, and in Grant’s mind, he felt that “success over Lee’s army” was “already assured.”[ii] (more…)

-

The Battle of the Wilderness

By the spring of 1864, changes were abound on the Union side. Three generals—Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Philip Sheridan—had become the preeminent leaders of the northern army. With Congress having revived the rank of lieutenant general, a rank last held by George Washington, President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to that rank and bestowed on him the title of general in chief.[i] While the North was in the ascendancy, the Confederate army had suffered through the winter. The Confederate Congress had eliminated substitution, which had allowed wealthy southerners to avoid conscription, and “required soldiers whose three-year enlistments were about to expire to remain in the army.”[ii] Even with Congress taking the extraordinary step of adjusting the draft age range to seventeen years old through fifty years old, the rebels still numbered fewer than half their opponents.[iii] Nonetheless, hope was not lost: a camaraderie pervaded the Southern army—particularly amongst the many veteran soldiers—which was perhaps best encapsulated in General Robert E. Lee’s saying that if their campaign was successful, “we have everything to hope for in the future. If defeated, nothing will be left for us to live for.”[iv] (more…)

-

The Battle of Chancellorsville

Joseph Hooker, at the head of the Army of the Potomac, was filled with confidence that he would not suffer the same fate as previous Union commanders facing Confederate General Robert E. Lee. While General Ambrose Burnside and General George McClellan earned their soldiers’ admiration with their leadership, they respectively fell at Fredericksburg and during the Peninsula Campaign and appeared to lack the incisive strategy to defeat Lee. (more…)

-

The Battle of Fredericksburg

Throughout 1862, the Union embraced a defensive, passive approach to prosecuting the Civil War—shying away from incisive troop movements and relentless pursuits even after battles that left Confederates fatigued and fleeing—while the Confederacy had most recently displayed its more aggressive strategy by its attack near the Antietam Creek in Maryland. At the helm of the Union army, and the epitome of its quiescent nature, stood General George McClellan: a man who had come under fire for his failed Peninsula Campaign and refusal to pursue Confederate General Robert E. Lee after the Battle of Antietam. The latter decision prompted action from the White House. President Abraham Lincoln, whom McClellan had labeled as the “Gorilla,” replaced McClellan with General Ambrose E. Burnside on November 7, 1862.[i] (more…)

-

The Battle of Antietam

Years before the Civil War started, Harpers Ferry, Virginia was the site of a federal armory that abolitionist John Brown raided with the hope of starting a revolution, causing distress throughout the Union that a revolution was in the making. In September 1862, Harpers Ferry became a thorn in the Union side yet again as Confederate General Stonewall Jackson raided and easily captured the town which occupied a strategically important position: the intersection of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers. After taking the town, Jackson and his men advanced toward Sharpsburg, Maryland and the bubbling Antietam Creek flowing past the outskirts of Sharpsburg.[i] (more…)

-

McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign

General George McClellan, commanding 400 ships, 100,000 men, 300 cannons, and 25,000 animals, prepared to execute one of the greatest invasions in the history of the American military: a plan to take the Virginia Peninsula, a perceived weak point in the Confederacy, and march on Richmond.[i] He brought hope to his men that they would be part of the greatest campaign not just of 1862 but in military history. However, President Abraham Lincoln anticipated that it would be a futile effort as the Union men would “find the same enemy, and the same, or equal [e]ntrenchments” on which they had fruitlessly tried to advance before.[ii] Worse than that, he feared that the Confederates would take advantage of the massive Union deployment on the Peninsula and march on Washington. (more…)