One night in late May 1861, “three negroes”—who said they were field hands, slaves—delivered themselves to the picket line at Fort Monroe in Virginia. Fort Monroe, sat on the peninsula between the York River and James River, had at its helm Brigadier General Benjamin F. Butler. The fugitive slaves had come to the fort to not only escape but to join the Union effort—to offer their skills and services to Butler and his soldiers. With no military policy in place for what to do with such fugitive slaves, it was a situation that raised difficult questions for Butler and the Union—of if, and how, to receive them—and the Confederacy—of how to stop their property and manpower from joining the enemy.

(more…)Tag: Slavery

-

The Civil War: Alexander H. Stephens: “Corner-Stone” Speech

March 21, 1861

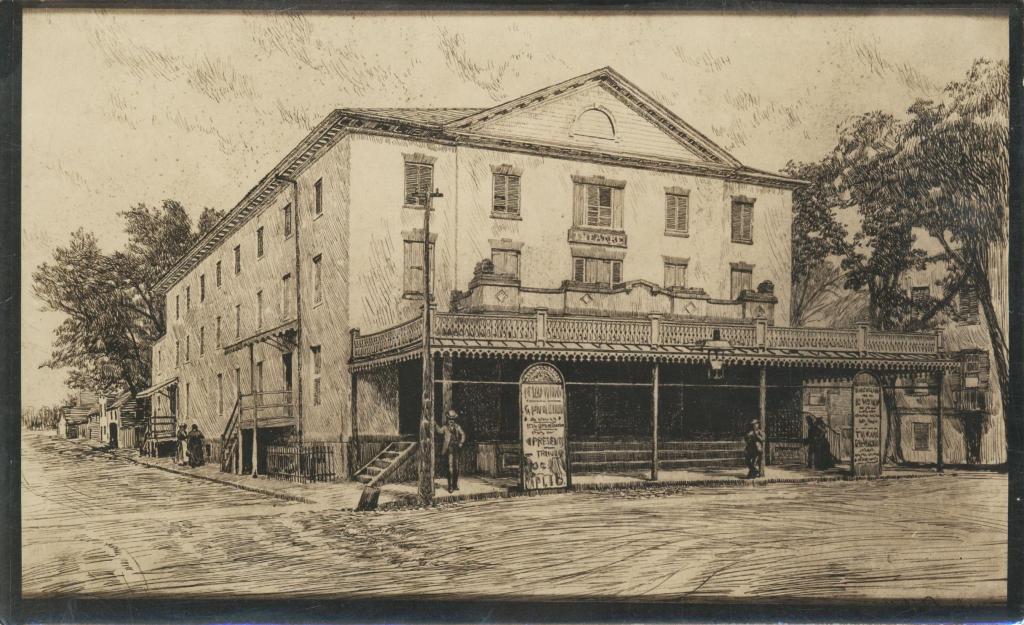

In Savannah, Georgia, at its Atheneum—a theater for shows and oratory—the vice-president of the Confederacy, Alexander H. Stephens, came to speak about the events leading up to states seceding from the Union and forming the Confederacy. The pace of these events had been swift and sure to cause consternation with questions abound as to what would happen next. To hear Stephens speak that day was to gain a better grasp of what was to come and perhaps a sense of comfort that all would be well.

(more…) -

The Civil War: Catherine Edmondston: Diary, December 27, 1860

December 27, 1860

Catherine Edmondston lived with her husband in North Carolina, and they operated a plantation there. During a visit to Aiken, South Carolina, to see her parents, she became a witness to the action surrounding South Carolina’s secession from the Union.

(more…) -

The Civil War: Benjamin F. Wade: Remarks in the U.S. Senate

December 17, 1860

Benjamin Wade, a Republican Senator from Ohio, rose to speak in the Senate. There were murmurs abound of averting the crisis—of stopping states from seceding from the Union. Some talked of forming a committee to explore the potential for a compromise between northern and southern states, even though no one knew what contours such a compromise could take. After all, for decades, Congress had been encapsulating compromises into bills, presidents had been signing those bills into law, and none of the laws resolved the tensions between the states.

(more…) -

The Civil War: Joseph E. Brown to Alfred H. Colquitt

December 7, 1860

A false dichotomy, or false dilemma, is a situation where a person is choosing from two options and believes that there are no other options available. The worst kind of false dichotomy occurs where there are not only other options but false information matriculating into the public discourse and creeping into the minds of people—particularly those people who are easily influenced; the kind of people who can come to believe anything, no matter how outlandish.

(more…) -

The Civil War: J.D.B. DeBow: The Non-Slaveholders of the South

Nashville, Tennessee

December 5, 1860

J.D.B. DeBow had run into a friend on the street and talked with him about how, in the South, even non-slaveholders benefitted from the region’s slave labor system. Then, promising to expand on what he said, he wrote this friend a letter, setting out in detail—in ten points—those benefits. As is common in political discourse, people use fallacious arguments to support their positions. DeBow was one such person.

(more…) -

The Civil War: James Buchanan: From the Annual Message to Congress

December 3, 1860

Washington City

James Buchanan was never going to avert the Civil War. But in his annual message to Congress, after the election of 1860, he scarcely even tried. Whereas most outgoing presidents use their last days in power to begin shaping their legacy, reflect on their time at the helm, and share their unique perspective on the country—and on the world—Buchanan was not like most outgoing presidents.

(more…) -

Constitution Sunday: “Publius,” The Federalist XLII [James Madison]

New-York Packet

January 22, 1788

One myth that persists about the founding of the American republic is that those men involved in framing the Constitution did not sufficiently account for the problems that could arise from slavery continuing into the Nineteenth Century. In reality, many of those men sought a way to slowly phase out the institution from American life; the trouble was crafting a compromise with their southern counterparts. With the slavery labor system as a bedrock for the southern economy, hammering out a compromise that replaced that system with one for wage labor was not likely. But some, like James Madison, saw an opportunity to first ban the importation of slaves and then move—as time passed—to outlaw slavery altogether. Men like Madison believed that this was the only way to proceed at the time that the Constitution was being drafted and then debated—as his article in the New-York Packet made clear.

(more…) -

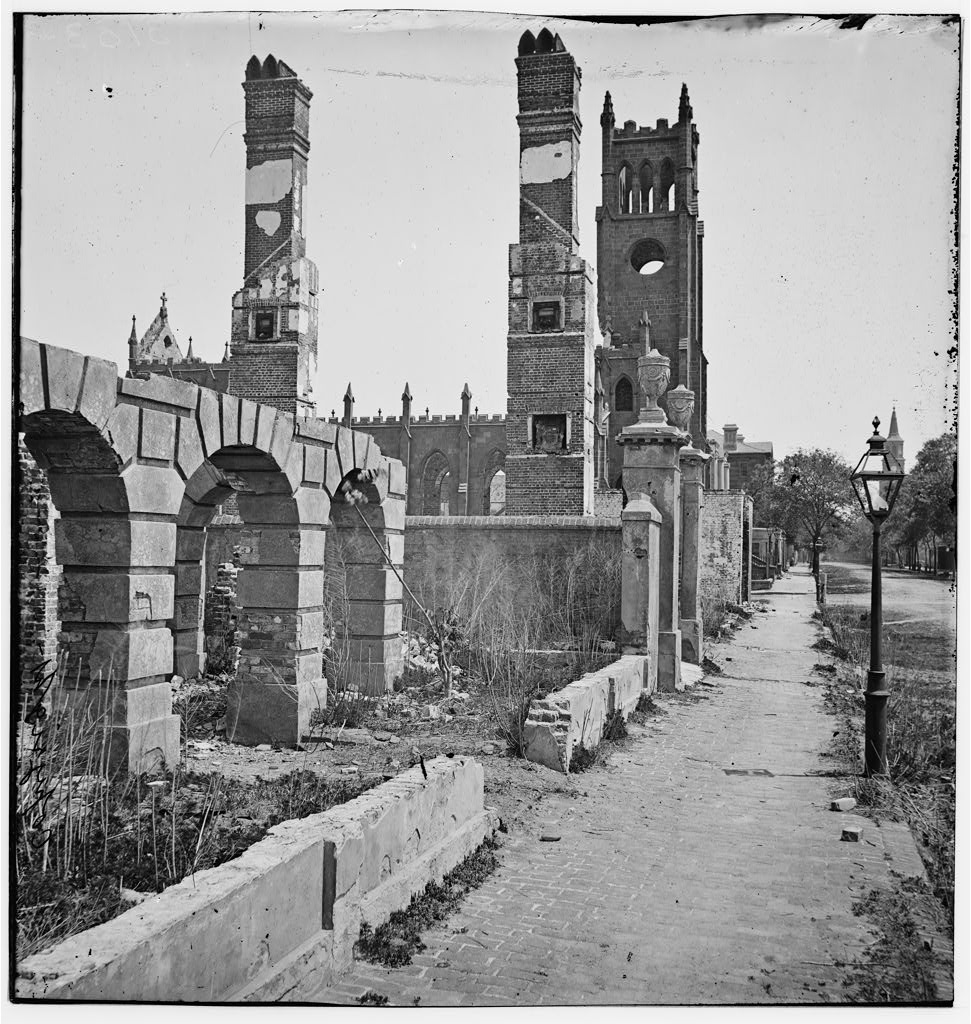

Reconstruction

The years after the Civil War, until 1877, were replete with novel uncertainties. The country had changed: the qualities that defined antebellum America had vanished; those who had been the most vocal before the war—soon-to-be Confederates—had seen their soapbox taken by the “Radical Republicans,” Republicans who sought to not only end slavery but to bring into effect equality amongst the races. Regardless of political party or geographic location, the country and its citizens had the task of reconstructing the United States, every one of them, and that task began before the Civil War’s end. President Abraham Lincoln spoke of his hope to reconcile the “disorganized and discordant elements” of the country, and he said: “I presented a plan of re-construction (as the phrase goes) which, I promised, if adopted by any State, should be acceptable to, and sustained by, the Executive government of the nation. I distinctly stated that this was not the only plan which might possibly be acceptable.”[i] Lincoln died four days later without fully setting forth his vision for how the nation may reconstruct itself, but events would soon render that vision—broad and ambiguous as it was—antiquated: soon after his death, the same federal government that had grown to enjoy extraordinary power (such as suspending the writ of habeas corpus) would go from having an authentic political genius, Lincoln, at its helm to having Andrew Johnson, a disagreeable at best (belligerent at worst) as executive; and not so long after Johnson took power, roving bands of the Ku Klux Klan acted in concert with state officials throughout the South to subjugate—by any means—those who had been freed.

(more…)