One night in late May 1861, “three negroes”—who said they were field hands, slaves—delivered themselves to the picket line at Fort Monroe in Virginia. Fort Monroe, sat on the peninsula between the York River and James River, had at its helm Brigadier General Benjamin F. Butler. The fugitive slaves had come to the fort to not only escape but to join the Union effort—to offer their skills and services to Butler and his soldiers. With no military policy in place for what to do with such fugitive slaves, it was a situation that raised difficult questions for Butler and the Union—of if, and how, to receive them—and the Confederacy—of how to stop their property and manpower from joining the enemy.

(more…)Tag: Virginia

-

The Civil War: John B. Jones: Diary, April 15-22, 1861

John B. Jones was a rare man in Philadelphia. In the spring of 1861, he thought he may be arrested for being a Confederate sympathizer. After all, he had been the editor of that city’s weekly newspaper, the Southern Monitor, which was supportive of the South. In April 1861, he left his home—arriving in Richmond, Virginia three days later. His diary from those days in Richmond reflected some of the conventional wisdom of the time—much of which has been long forgotten—about how the Confederacy may have taken shape not as a group of states but as an empire. He also wrote about some unconventional wisdom of the time: how the North was not just preparing for an immediate war; it was preparing for a complete and ruthless victory.

(more…) -

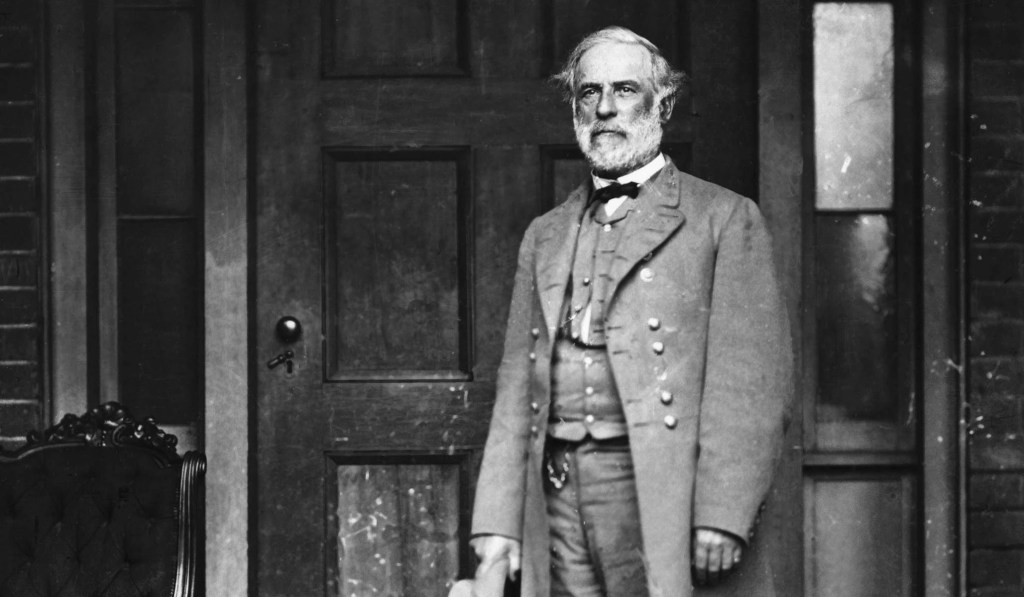

The Civil War: Robert E. Lee to George Washington Custis Lee

January 23, 1861

While Robert E. Lee was serving as the acting commander of the Department of Texas at Fort Mason, in Texas, he wrote to his son George Washington Custis Lee of the events unfolding in the east—southern states beginning to secede amid antagonism from the north.

(more…) -

The Civil War: Henry Adams to Charles Francis Adams Jr.

January 8, 1861

A few weeks after Henry Adams wrote to his brother Charles Francis Adams Jr. about the scenes playing out post-election in Washington, D.C., he wrote again—this time about the potential for warfare to soon begin.

(more…) -

The Civil War: George Templeton Strong: Diary, November 20-December 1, 1860

November 20, 1860 to December 1, 1860

New York City

State laws often have an outsized influence on discussions of national politics. This is despite the fact that one state’s laws have no binding effect in other states; then, add to that the fact that some states will pass laws with little intent or resources backing the enforcement of those laws. Those are the laws that can be nothing more than pieces of paper as props in the political theater. But, when those laws touch on an inflammatory issue, the practicalities of the laws become irrelevant. The only thing that matters then is that the laws exist and that they could spread to other states, disrupting the status quo and creating concern as to the path that the nation and its states have chosen.

(more…) -

Constitution Sunday: David Ramsay to Benjamin Lincoln

Charleston, South Carolina

January 29, 1788

A letter from a South Carolinian to a Massachusettsan—and from a budding historian to a Revolutionary War hero—captured the spirit of the moment as South Carolina was preparing to assemble its convention to consider the Constitution. David Ramsay, who would soon publish a two-volume book about the American Revolution, wrote to Benjamin Lincoln of the recent happenings in South Carolina’s legislature and the tenor of the time as states were analyzing the potential for coexisting with a federal government.

(more…) -

Constitution Sunday: “An Old State Soldier” I

Virginia Independent Chronicle (Richmond)

January 16, 1788

A former soldier sought to inform his fellow Virginians about the merits of the draft Constitution, and his fellow Virginians would be incorrect if they assumed that he was merely a soldier and would know nothing about the wisdom needed for setting up a new government. He described himself as a “fellow-citizen whose life has once been devoted to your service, and knows no other interest now than what is common to you all, solicits your attention for a new few moments on the new plan of government submitted to your consideration.” He was all too aware that some of the more intellectual arguments had already been made but also that his perspective would serve “to contradict some general opinions which may have grown out of circumstances too dangerous to our reputations to remain unanswered.”

(more…) -

The Legacy of Robert E. Lee

No figures in American history earn universal admiration. As years—and generations—pass, legacies change. As morals, priorities, and political issues evolve, so do understandings of those people in the past who brought change—good, bad, or otherwise—to the country. For some figures, like Abraham Lincoln, whose authentic genius is admired generation after generation, their merit is questioned only by those who unreasonably say the great should have been greater. For others, it becomes much more varied and nuanced, and for Robert E. Lee, his legacy has always differed depending on the part of the country where his legacy is measured and the tenor of the moment. This is because, perhaps more than even Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Lee became a symbol of the Confederacy—with all its ills but also its potential for what might have been.

(more…) -

The Revolution: Thomas Jefferson on the Draft Articles of Confederation (Part II)

The Autobiography. By: Thomas Jefferson

July 30, 1776 – August 1, 1776

How the colonies would get along with each other was always going to be a monumental challenge. And, when the nation was born, there was tension between delegates and their states in setting up the framework for how the colonies would vote. With states such as Massachusetts and Pennsylvania being much larger in size and population, smaller states such as Rhode Island could justifiably fear that confederating with the colonies would bring more harms than benefits. However, to the chagrin of larger states, in the draft Articles of Confederation, at Article XVII, it stated: “In determining questions each colony shall have one vote.”

(more…) -

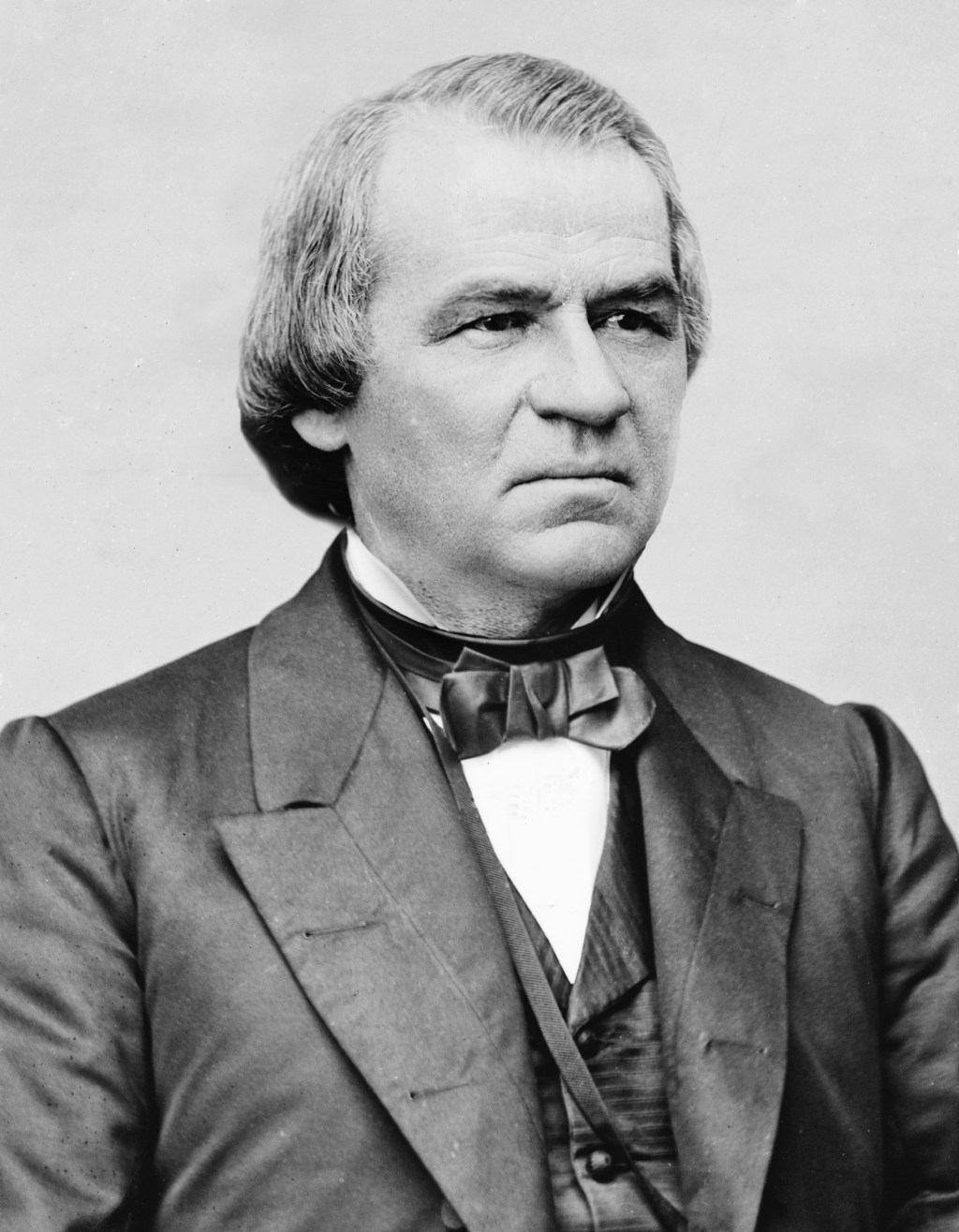

A Nation Reborn

In the same way that the Second World War would reshape the globe in the Twentieth Century, the Civil War reshaped America for the remainder of the Nineteenth Century. Veterans of both wars came to define their respective generations and rise to positions of power: just as Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s meteoric rise culminated in him becoming President three years after the war, General Dwight D. Eisenhower would find himself being elected President seven years after the war of his generation. Lesser generals also worked their way into office—some of those offices being elected and others being executive offices of companies in the emerging industries following the wars—but that would occur over the course of decades: the last Civil War veteran to reach the presidency, William McKinley, occupied the White House as the Nineteenth Century faded into the Twentieth. As ever, those who held power determined the direction of the country’s future. In the weeks and months following the end of the Civil War, and President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, people in power would be sketching out the contours of a post-war America; and it was then, at that nascent stage of the newly reborn nation’s life, that new factions emerged—factions that would vie for weeks, months, and even years to cast the die of America in their own image and either keep, or make, the nation they wished to have.

(more…)