Conceptualizing the Civil War’s end, even during the opening months of 1865, was nearly impossible: who could imagine Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendering himself and his men to the custody of the Union army? How many members of the Confederate government would be taken prisoner and be tried for treason and any number of other crimes for defying the United States federal government? What would come from an Abraham Lincoln presidency that was not entirely consumed with prosecuting the war? And perhaps the most troubling question of all: how, after all the fratricidal blood shed and destruction wrought against one another, could the Confederate states be readmitted and the country continue to exist? On April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, when General Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, the contours of a post-war America were beginning to be defined—and for the Confederates, it appeared, with Lee’s surrender, that the future would be one of subjugation to the northern states. (more…)

Tag: Virginia

-

Tightening the Cordon

By the end of 1864—with Union General William Tecumseh Sherman having cut his way through Georgia, Union General Ulysses S. Grant having confined Confederate General Robert E. Lee to a defensive position in Virginia, and President Abraham Lincoln having won his bid for re-election—the Confederacy was desperate for any sign of encouragement. While the rhetoric from Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Vice President Alexander Stephens had remained buoyant, and despite newspaper headlines throughout the South continuing to cheer for the cause, the Confederacy was nowhere near the crest it had enjoyed in 1863. Having lost the chance to put the Union on the defensive that year, the rebels now found their western and southern borders closing in on them. If ever there was going to be a negotiated peace, the chances of it occurring were rapidly diminishing as 1865 dawned. (more…)

-

The Battle of the Crater

Although the Battle of Petersburg had ended with the Confederates retaining control of the city, the Union had started its siege; a strategy that had been effective at Vicksburg but required months to succeed. Prolonged trench warfare was virtually certain, and, despite federal efforts to disrupt Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s supply lines, many of the northern troops lacked the energy that they possessed during the early part of the war and were unable to destroy the railroads surrounding Petersburg so completely that the rebels could not repair them. While the beginning of 1864 had shown the Union’s ability to take rebel territory, from June to the end of July, the momentum of the war took on a pendular quality as both sides seemed to come ever closer to victory. (more…)

-

The Battle of Petersburg

Consistent with every other battle in Ulysses S. Grant’s career that left him with a discouraging result, he had drawn up a plan to avenge the disaster at Cold Harbor and put the Confederates on their heels. (more…)

-

The Battle of Cold Harbor

Within a dozen miles of Richmond sat the dusty crossroads of Cold Harbor. The town, with its tavern and “triangular grove of trees at the intersection of five roads,” would be the next stop in Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign in Virginia to defeat Robert E. Lee. There, approximately 109,000 Union troops sat ready to take on around 59,000 entrenched rebels.[i] The battle was likely to only be a continuation of the “relentless, ceaseless warfare” that had characterized Grant’s campaign into Virginia throughout 1864, and in Grant’s mind, he felt that “success over Lee’s army” was “already assured.”[ii] (more…)

-

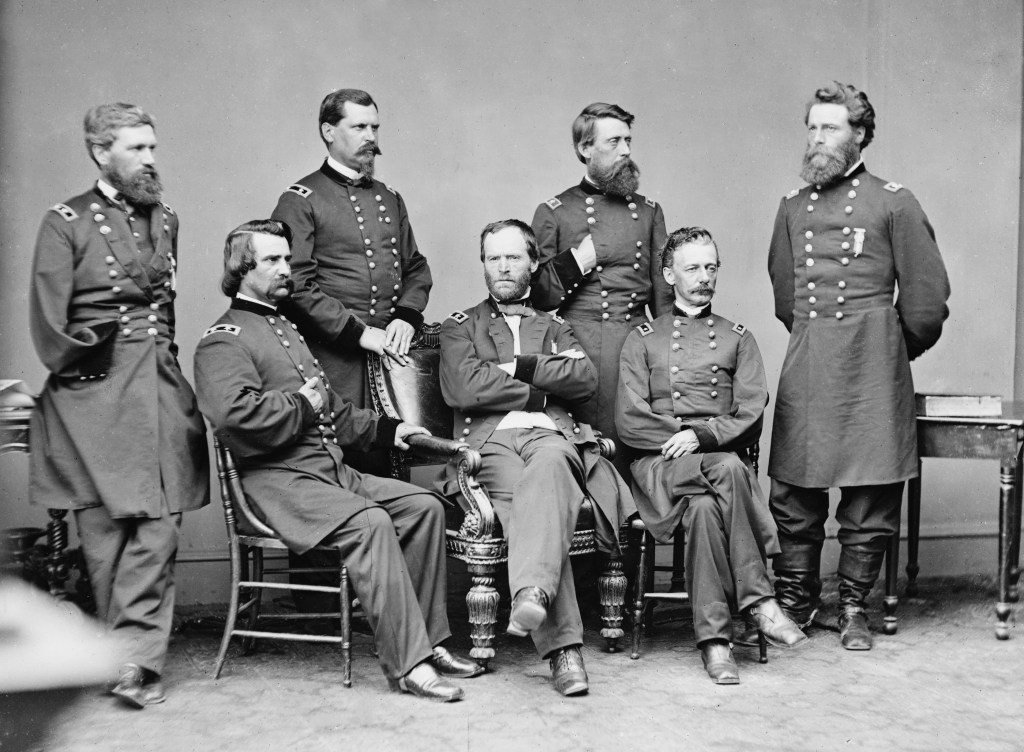

The Battle of the Wilderness

By the spring of 1864, changes were abound on the Union side. Three generals—Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Philip Sheridan—had become the preeminent leaders of the northern army. With Congress having revived the rank of lieutenant general, a rank last held by George Washington, President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to that rank and bestowed on him the title of general in chief.[i] While the North was in the ascendancy, the Confederate army had suffered through the winter. The Confederate Congress had eliminated substitution, which had allowed wealthy southerners to avoid conscription, and “required soldiers whose three-year enlistments were about to expire to remain in the army.”[ii] Even with Congress taking the extraordinary step of adjusting the draft age range to seventeen years old through fifty years old, the rebels still numbered fewer than half their opponents.[iii] Nonetheless, hope was not lost: a camaraderie pervaded the Southern army—particularly amongst the many veteran soldiers—which was perhaps best encapsulated in General Robert E. Lee’s saying that if their campaign was successful, “we have everything to hope for in the future. If defeated, nothing will be left for us to live for.”[iv] (more…)

-

The Battle of Gettysburg

By the spring of 1863, the Union had given the Confederacy every reason to remain defensive: for the duration of the war, federal troops had invaded points throughout the south forcing the rebels to shift to the location of each incision. Allowing this dynamic to continue to play out meant the only way for a Confederate success was a negotiated peace. On May 15, the southern brain trust, including General Robert E. Lee and President Jefferson Davis, convened in Richmond to discuss strategy. Lee proposed that he lead an effort that would remove the threat to Richmond, throw the Yankees on their heels, spell political doom for the Republicans (led by Abraham Lincoln in the White House), open up the possibility of Britain or France recognizing the Confederacy, and, at worst, an armistice that resulted in the Confederate States of America coexisting with the United States.[i] While Postmaster-General John Reagan and other Confederates felt that Lee should have sent troops to protect Vicksburg and the west from the trouble Ulysses S. Grant and his men were causing, Lee did not want to oblige the Confederacy to remain on the defensive but instead introduce the “prospect of an advance” as it would change “the aspect of affairs.”[ii] (more…)

-

The Battle of Chancellorsville

Joseph Hooker, at the head of the Army of the Potomac, was filled with confidence that he would not suffer the same fate as previous Union commanders facing Confederate General Robert E. Lee. While General Ambrose Burnside and General George McClellan earned their soldiers’ admiration with their leadership, they respectively fell at Fredericksburg and during the Peninsula Campaign and appeared to lack the incisive strategy to defeat Lee. (more…)

-

The Battle of Antietam

Years before the Civil War started, Harpers Ferry, Virginia was the site of a federal armory that abolitionist John Brown raided with the hope of starting a revolution, causing distress throughout the Union that a revolution was in the making. In September 1862, Harpers Ferry became a thorn in the Union side yet again as Confederate General Stonewall Jackson raided and easily captured the town which occupied a strategically important position: the intersection of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers. After taking the town, Jackson and his men advanced toward Sharpsburg, Maryland and the bubbling Antietam Creek flowing past the outskirts of Sharpsburg.[i] (more…)

-

The Second Battle of Bull Run

After General George McClellan’s campaign to take Richmond fell flat, he became even more disenchanted with the Lincoln administration but vowed that if provided with 50,000 men, he would mount another attack on the Confederate front.[i] Whether a man who had “lost all regard and respect” for President Lincoln and had called the Lincoln administration “a set of heartless villains” was dedicated to restoring the Union became a question for years to come, and Lincoln recognized that even if he sent 100,000 men, McClellan would find Confederate General Robert E. Lee to have 400,000.[ii] Regardless, a Union general from the Western Theater, John Pope, had come to the Eastern Theater prepared to replace McClellan as the top commander in the East and take on the Confederates with the tenacious and fearless approach to fighting that had characterized the western battles.[iii] (more…)