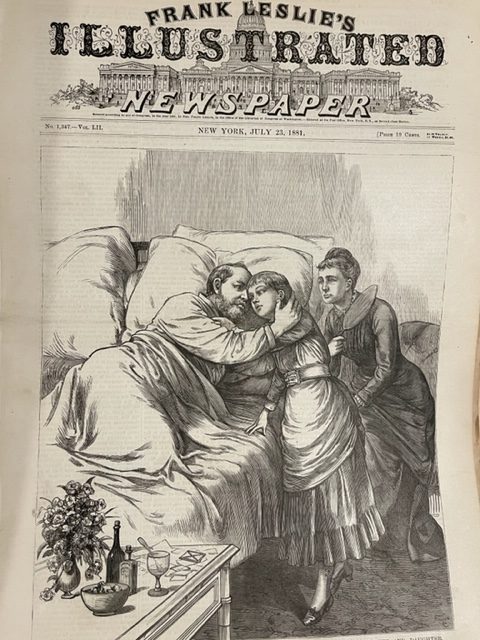

In the late afternoon, during the summer, a thunderstorm rolled its way through the nation’s capital. Although it first had the effect of cooling the thick Washington air, the effect was fleeting. By 10 o’clock that night, the President could have hope for relief: a new apparatus—rumored to be quite effective against the oppressively humid air of India—had arrived. Staff assembled V-shaped troughs, made of zinc and “filled with ice and water,” and placed them under the windows of the President’s room.[i] The water lessened the humidity, and the ice cooled the air entering the room through the windows.[ii] The President’s pulse, temperature, and respiration satisfied his physicians, and there was optimism that “the worst was over.”[iii] It had been several weeks since the attempted assassination, and the 20th President of the United States, James Garfield, was having his secretaries attend to the pressing matters of the country as he rested.[iv] His wife and children visited his bedside, and his daughter, Mollie, “nestled her fresh face in his beard,” keeping her composure just as her mother did.[v] The President “kissed her and stroked her hair, and then she took a seat near her mother” when the “boys came in presently with manful bearing and remained a few minutes.”[vi] The cooling apparatus, the doctors said, was not giving “entire satisfaction,” and a new device—one that was “similar to that used in the mines to cool the air and send it into the chamber through the registers”—was set to be installed to relieve the President from his symptoms.[vii]

(more…)Tag: Washington DC

-

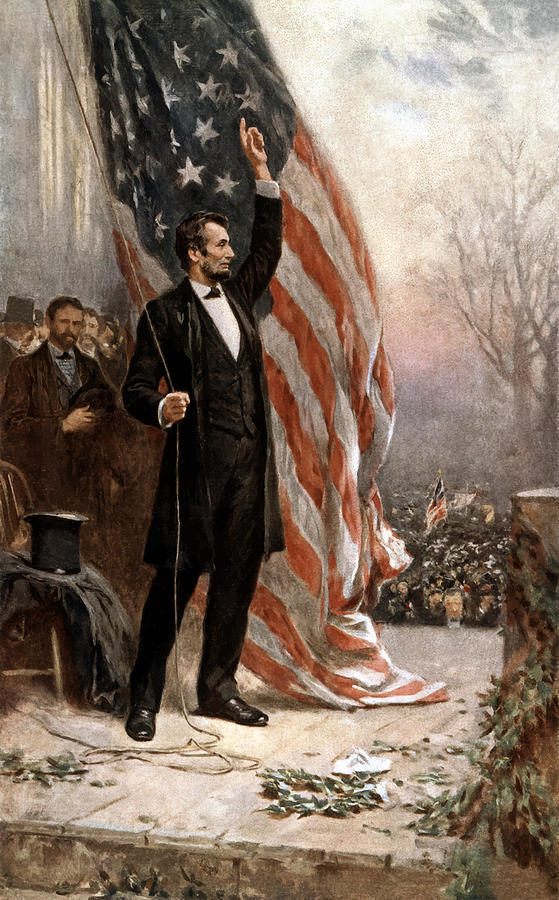

The Second Father

In February 1861, Abraham Lincoln traveled to the Western Railroad Depot carrying his trunk tied with a rope and with the inscription, “A. Lincoln, White House, Washington, D.C.” Friends and family prepared him for the train ride from Illinois to Washington which would take twelve days and bring the President-elect into contact with tens of thousands of citizens. Lincoln had been “unusually grave and reflective” as he lamented “parting with this scene of joys and sorrows during the last thirty years and the large circle of old and faithful friends,” and when he went to his law partner for sixteen years, Billy Herndon, he assured him that his election to the presidency merely placed a hold on his partnership role: “If I live I’m coming back some time, and then we’ll go right on practising law as if nothing had ever happened.” As he stood on his private train car and addressed the crowd of well-wishers, the sentiment was no less heartfelt: “My friends—No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. . . . I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.” And so, with the crowd moved to tears, Lincoln would leave Springfield for the last time in his life with the train slowly moving “out of the sight of the silent gathering.” Within the train car, furnished with dark furniture, “crimson curtains, and a rich tapestry carpet,” Lincoln “sat alone and depressed” without his usual “hilarious good spirits.” (more…)

-

The Second Battle of Bull Run

After General George McClellan’s campaign to take Richmond fell flat, he became even more disenchanted with the Lincoln administration but vowed that if provided with 50,000 men, he would mount another attack on the Confederate front.[i] Whether a man who had “lost all regard and respect” for President Lincoln and had called the Lincoln administration “a set of heartless villains” was dedicated to restoring the Union became a question for years to come, and Lincoln recognized that even if he sent 100,000 men, McClellan would find Confederate General Robert E. Lee to have 400,000.[ii] Regardless, a Union general from the Western Theater, John Pope, had come to the Eastern Theater prepared to replace McClellan as the top commander in the East and take on the Confederates with the tenacious and fearless approach to fighting that had characterized the western battles.[iii] (more…)

-

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff

By the end of 1861, the Union changed its commander but also suffered its third major defeat; this one northwest of Washington at Ball’s Bluff on the banks of the Potomac River. (more…)

-

The First Battle of Bull Run

Three months after the firing on Fort Sumter, the Confederacy and Union had produced armies capable of fighting and mobilized to northern Virginia; roughly halfway between Washington and Richmond. There, near a “sluggish, tree-choked river” known as Bull Run, the first major battle following the secession of the South would occur.[i] (more…)

-

On to Richmond

Although the Confederacy had awakened the North’s spirit by initiating hostilities at Fort Sumter, both sides could have still hoped for reconciliation. While some advocated for immediate peace, others wished for a full prosecution of war against the South, viewing its expanding secession as nothing short of treason. By the end of spring 1861, there was a decisive answer to the question of whether there would soon be peace. (more…)

-

The Awakened Giant

The news from Fort Sumter spread throughout the country, and its coming awakened a restless energy in the North. That energy ignited patriotism and a new sense of collectivism throughout northern cities and states that would lead to a then-unparalleled war effort directed against the Confederacy. (more…)

-

The Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

From the time of the Election of 1860 to the beginning of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, there was uncertainty as to how Lincoln and his administration would handle the growing Confederacy and existential crisis facing the country. (more…)

-

The Compromise of 1850

“United States Senate, A.D. 1850.” By: Peter F. Rothermel. Upon President Zachary Taylor taking office, he sent a message to Congress deploring the sectionalism that was pervading the country. See David Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861, 91. He looked to George Washington’s warnings against “characterizing parties by geographical discriminations,” which appeared by 1849 to be a prescient warning. Id. citing James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents (11 vols.; New York, 1907), V, 9-24. President Taylor offered hope for northerners and those Americans who wanted to preserve the Union with his vow: “Whatever dangers may threaten it [the Union] I shall stand by it and maintain it in its integrity.” David Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861, 91 citing James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents (11 vols.; New York, 1907), V, 9-24. (more…)

-

A Deadlocked and Destructive Congress

The United States Capitol in 1848. Unknown Photographer, credit Library of Congress. During President James Polk’s administration, Congress grappled with resolving sectional tension arising out of whether slavery would be extended to newly acquired land from Mexico as well as the Oregon territory. Congress did not resolve that sectional tension but exacerbated it in what may have been one of the most deadlocked and destructive Congresses in American history. (more…)