March 21, 1861

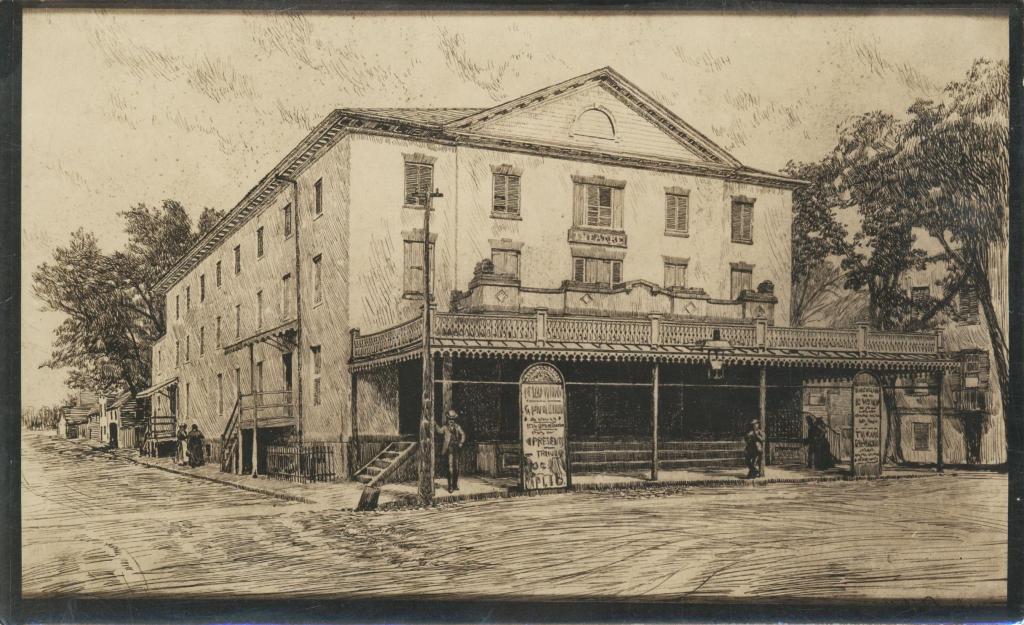

In Savannah, Georgia, at its Atheneum—a theater for shows and oratory—the vice-president of the Confederacy, Alexander H. Stephens, came to speak about the events leading up to states seceding from the Union and forming the Confederacy. The pace of these events had been swift and sure to cause consternation with questions abound as to what would happen next. To hear Stephens speak that day was to gain a better grasp of what was to come and perhaps a sense of comfort that all would be well.

To Stephens, the crowd and he had gathered “in the midst of one of the greatest epochs in our history,” and the preceding ninety days would “mark one of the most memorable eras in the history of modern civilization.” And it was a significant crowd at the Atheneum that day: many spilled out into the street hoping to catch any of the speech that they could. In fact, just as Stephens began speaking, those individuals who had gathered outside the building, for there was no more room in the Atheneum, called “for the speaker to go out,” and “that there were more outside than in.”

Even though the mayor then rose to say that Stephens’ health did not permit him to speak in the open air, Stephens said that he would set any such health issues aside and heed to the audience’s preference as to where he spoke. In the Atheneum, a group of women—“a large number of whom were present”—said they would not have been able to hear him if he went outside, and Stephens said that he would accommodate the ladies and remain inside.

To applause, he then spoke of the new constitution—the Confederate one—which he said was “decidedly better than the old.” He spoke of its feature that cabinet ministers and heads of departments had the “privilege of seats upon the floor of the Senate and House of Representatives,” an arrangement that allowed them to speak on “behalf of its entire policy, without resorting to the indirect and highly objectionable medium of a newspaper.” “Rapturous applause” filled the Atheneum.

Then, the crowd outside further clamored that they wished to hear Stephens speak, but when the mayor and police called for order to be restored and for the speech to go on, the clamor subsided.

Stephens resumed his speech, noting that the Constitution—the Union’s—was based on the prevailing idea that enslaving Africans violated “the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically.” “Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong,” he said. “They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the ‘storm came and the wind blew.’”

He said that the “new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” The crowd applauded.

Stephens boasted that this, “our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” It had been a truth slow to develop, like any scientific truth, he said, but a truth nonetheless.

He concluded by speaking of the future, and that future consisted of “presenting to the world the highest type of civilization ever exhibited by man.” When he took his seat, there was a “burst of enthusiasm and applause, such as the Atheneum has never had displayed within its walls, within ‘the recollection of the oldest inhabitant.”

The Savannah Republican published a reporter’s summary of Stephens’ remarks at the Atheneum. And only after the war—after the failure of the Confederacy and at a time when the country was grappling with what the war meant and how the country would proceed after it—did Stephens take issue with the reporting. He took issue with it only after he was off the wave that had carried him into Savannah that day; a wave that had been building for some time and was reaching its crest just then, when it looked like the nascent Confederacy was establishing itself and on a trajectory to sustained independence. But after that wave came crashing down with the end of the war, Stephens and Jefferson Davis and any other former Confederate who held that failed cause close to heart could no longer be open about what their aims were during the heady days when they were in control: the times had changed; the cause had failed; the tables had turned.

It was with that backdrop that Stephens claimed, after the war, that the reporting of his speech at the Savannah Atheneum contained “several glaring errors”—including the notion that the cornerstone of the Confederacy was slavery. But the fact remained that nine days before the speech in Savannah, Stephens had orated in Atlanta and said there that the Confederacy’s founders had “solemnly discarded the pestilent heresy of fancy politicians, that all men, all races, were equal, and we had made African inequality and subordination, and the equality of white men, the chief corner stone of the Southern Republic.”

Leave a comment