As time passes and collective morals change, the legacies of prominent figures in American history often evolve. The context in which these individuals earned their place in American memory becomes increasingly difficult to uncover.

Tag: Ulysses Grant

-

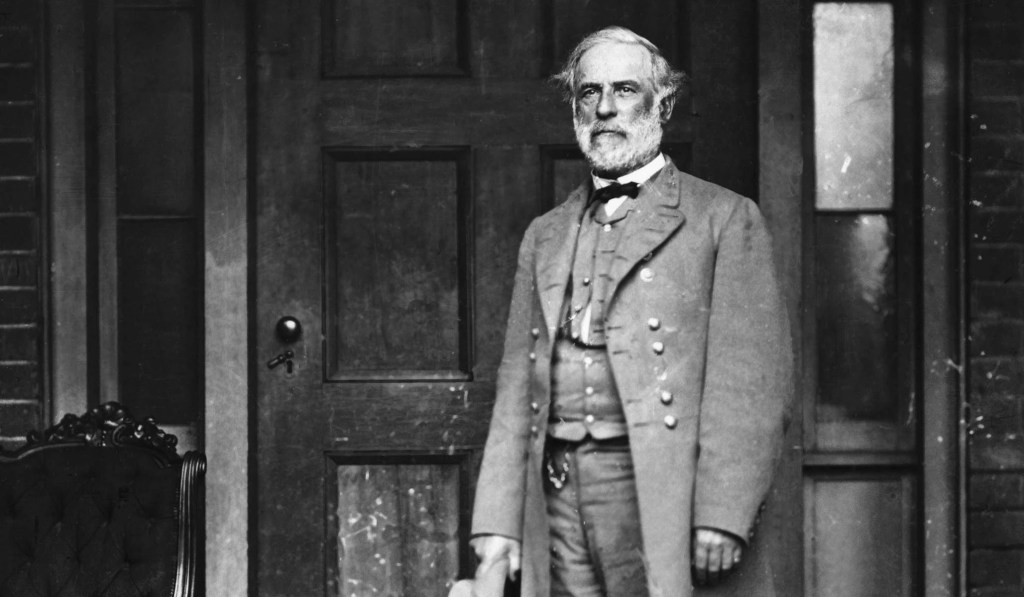

The Legacy of Robert E. Lee

No figures in American history earn universal admiration. As years—and generations—pass, legacies change. As morals, priorities, and political issues evolve, so do understandings of those people in the past who brought change—good, bad, or otherwise—to the country. For some figures, like Abraham Lincoln, whose authentic genius is admired generation after generation, their merit is questioned only by those who unreasonably say the great should have been greater. For others, it becomes much more varied and nuanced, and for Robert E. Lee, his legacy has always differed depending on the part of the country where his legacy is measured and the tenor of the moment. This is because, perhaps more than even Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Lee became a symbol of the Confederacy—with all its ills but also its potential for what might have been.

(more…) -

The Legend of Winfield Scott Hancock

War heroes earn respect through their service. The Civil War brought out more heroes than perhaps any other war in American history. They were men who served their country at its inflection point, and they could be assured that their time on the battlefield could translate to time in public office. General Winfield Scott Hancock was but one example. He was “a patriotic hero, a stainless gentleman, and an honest man.”[i] He became one of the greatest Generals in the war: one that the soldiers, officers, and citizens were glad to have. He got out from under a famous name and created his own legacy, becoming a regular name in the wartime newspapers. But there was still a question of whether his post-war career would be as glamorous as his time during the war. Although he had a reputation for “honest heroism and personal character,” he was a Democrat; and at a time when Democrats simply could not expect to win the Presidency.[ii]

(more…) -

The Rise of James Garfield

It was a time of oratory and a time when Ohioans became President. James Garfield was a product of the time. He was born into “a poor family” and “an intellectual in love with books.”[i] He attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute as a student and janitor, and by the following year, he became an assistant professor.[ii] Garfield was a man who treasured intellect. When William Dean Howells came to Garfield’s home in Hiram, Ohio in 1870, he sat on the porch and told a story about New England’s poets; Garfield “stopped him, ran out into his yard, and hallooed the neighbors sitting on their porches: ‘He’s telling about Holmes, and Longfellow, and Lowell, and Whittier.’”[iii] At a time when the Midwest fostered “a strong tradition of vernacular intellectualism” that manifested itself in “crowds for the touring lectures, the lyceums, and later the Chautauquas,” the neighbors gathered and listened “to Howells while the whippoorwills flew and sang in the evening air.”[iv]

(more…) -

The Election of 1884

The Democratic Party was in turmoil. Its candidates were not winning, and many of its ideas had fallen out of favor. It was a long way from the days of the Party’s founding: Andrew Jackson and his disciple, Martin Van Buren, held power for the twelve years spanning 1829 to 1841 and—into the 1840s and 1850s—James Polk, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan continued to lead the Party into the White House albeit against candidates from the newly-formed and then soon-to-be-disbanded Whig Party. Then, following the emergence of the Republican Party—an emergence which culminated in its candidate, Abraham Lincoln, prevailing in the elections of 1860 and 1864—Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President and then successor as President, oversaw a one-term presidency which came to an end in 1869. Johnson, partly because he was serving between two titans of the century (Lincoln and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant), was always going to struggle to earn admiration but, unlike Lincoln and Grant, Johnson was technically a Democrat, and perhaps because he was so thoroughly shamed for his actions as President, the Party would scarcely recognize him as a member. Whether a result of Johnson’s malfeasance or not, following Johnson’s presidency came an era of Republican dominance: Republican Grant won two consecutive terms, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes secured a succeeding term, Republican James Garfield then was victorious, and following his assassination, Republican Chester Arthur served out the remainder of that term. That brought the parties and the country to 1884. As the election of 1884 approached, it had been decades since a strong, effective Democrat—a Democrat who embodied the Party’s principles and would be a standard bearer for the Party, unlike the postbellum Democratic President, Johnson, or the last antebellum one, Buchanan—held office, and for Democrats to win this election, it would take someone special; someone who would be transformative even if only in a way that was possible at the time. As fortune would have it, it could not be a wartime presidency or a presidency that birthed fundamental change in American government, but that was because the circumstances of the era did not call for such a President; it could, however, be a presidency that tackled one of the biggest issues of the time: corruption.

(more…) -

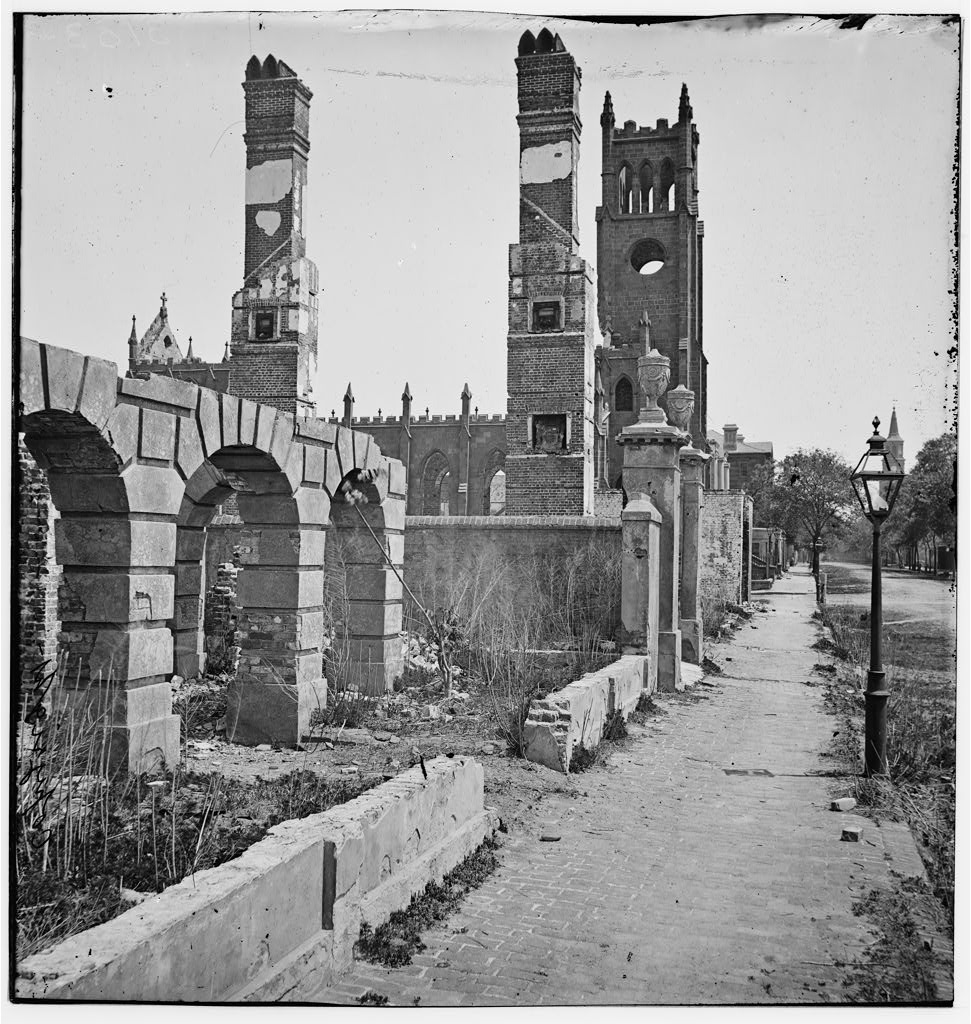

Reconstruction

The years after the Civil War, until 1877, were replete with novel uncertainties. The country had changed: the qualities that defined antebellum America had vanished; those who had been the most vocal before the war—soon-to-be Confederates—had seen their soapbox taken by the “Radical Republicans,” Republicans who sought to not only end slavery but to bring into effect equality amongst the races. Regardless of political party or geographic location, the country and its citizens had the task of reconstructing the United States, every one of them, and that task began before the Civil War’s end. President Abraham Lincoln spoke of his hope to reconcile the “disorganized and discordant elements” of the country, and he said: “I presented a plan of re-construction (as the phrase goes) which, I promised, if adopted by any State, should be acceptable to, and sustained by, the Executive government of the nation. I distinctly stated that this was not the only plan which might possibly be acceptable.”[i] Lincoln died four days later without fully setting forth his vision for how the nation may reconstruct itself, but events would soon render that vision—broad and ambiguous as it was—antiquated: soon after his death, the same federal government that had grown to enjoy extraordinary power (such as suspending the writ of habeas corpus) would go from having an authentic political genius, Lincoln, at its helm to having Andrew Johnson, a disagreeable at best (belligerent at worst) as executive; and not so long after Johnson took power, roving bands of the Ku Klux Klan acted in concert with state officials throughout the South to subjugate—by any means—those who had been freed.

(more…) -

The Election of 1876

In celebrating America’s first centennial, on July 4, 1876, one must have recalled the tumult of that century: a war to secure independence, a second war to defend newly-obtained independence, and then a civil war the consequences of which the country was still grappling with eleven years after its end. But there also had been extraordinary success in that century, albeit not without cost; by the 100-year mark, the country had shown itself and the world that its Constitution—that centerpiece of democracy—was holding strong (with 18 Presidents, 44 Congresses, and 43 Supreme Court justices already having served their government by that time), and the country had expanded several times over in geographic size, putting it in command of a wealth of resources as its cities, industries, and agriculture prospered. Several months after the centennial celebration was the next presidential election, and during the life of the country, while most elections had gone smoothly, some had not—the elections of 1800 and 1824 were resolved by the House of Representatives choosing the victor as no candidate secured a majority of Electoral College votes and the election of 1860 was soon followed by the secession of Southern states. And yet, even with those anomalous elections in view, the upcoming election of 1876 was to become one unlike any other in American history.

(more…) -

The Election of 1872

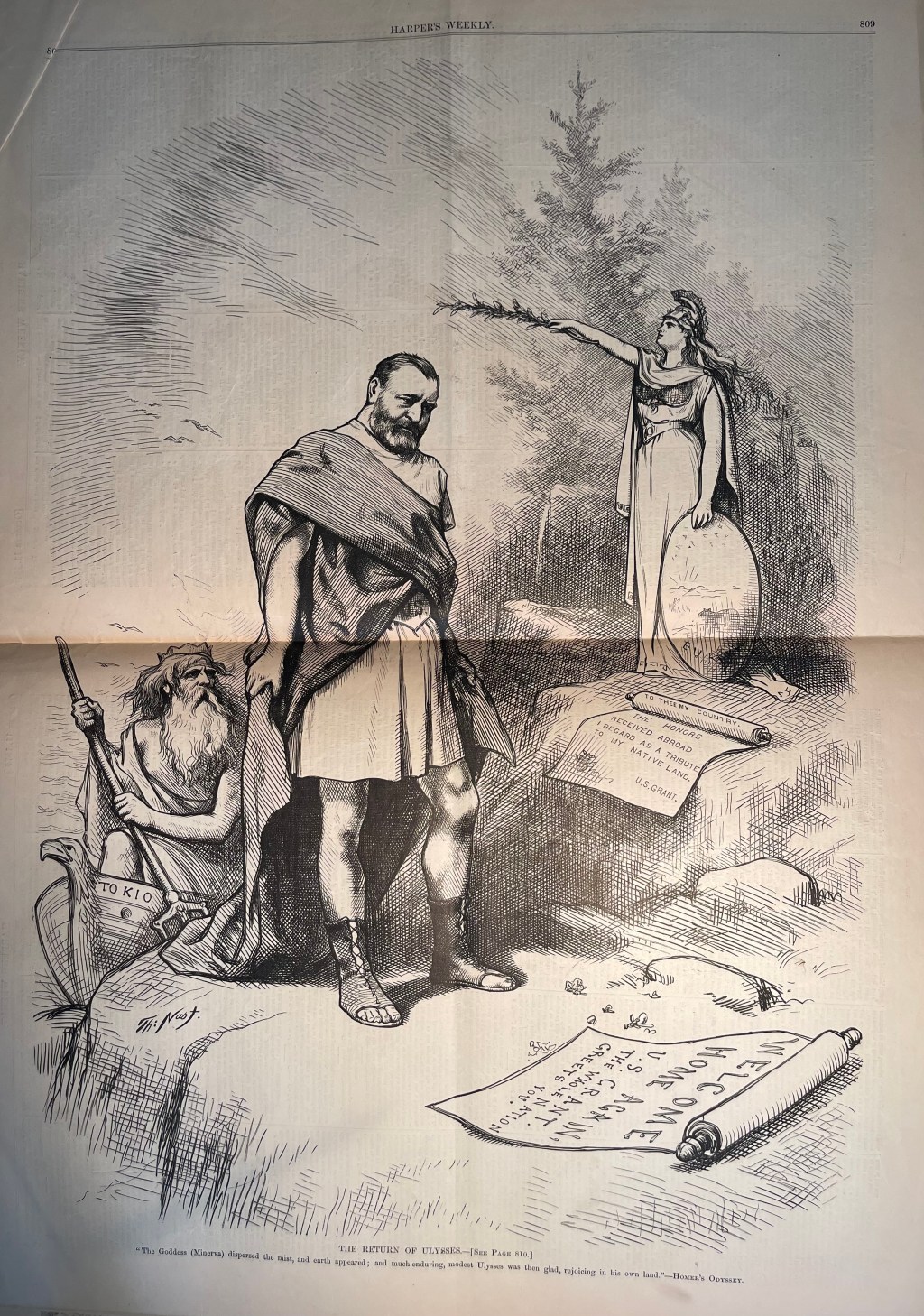

From the time that Ulysses S. Grant became a household name in America—during the Civil War—and particularly following Lincoln’s assassination, there was no more popular American in the remainder of the Nineteenth Century. The presidential election of 1868 showed the level of support that Grant had: although it was his first election, he won the entirety of the Midwest and New England and even took six of the former Confederate states. He was always going to be a formidable opponent. As the election of 1872 approached, it became clear that Grant, a Republican, would not have to vie for re-election against a candidate with the stature of a fellow former general or even a well-established politician; instead, his challenger would be the founder and editor of a newspaper: Horace Greeley, a Democrat. Although Greeley had one term in the House of Representatives at the end of the 1840s, his following stemmed not from his brief time as a politician but rather the incisive pieces that he wrote and published in his newspaper, the New-York Tribune. As loyal as his readers were, there remained a question whether Greeley’s following could grow to unseat the man who still, seven years after the war, was viewed as bringing peace and prosperity to the country.

(more…) -

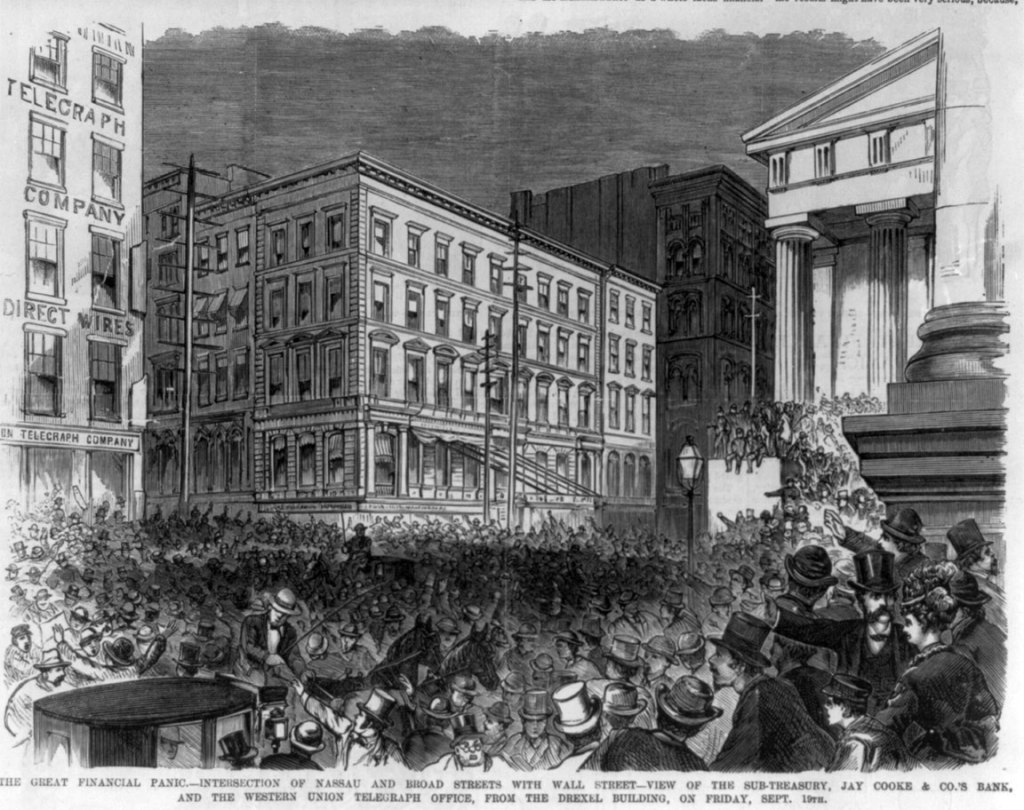

The Panic of 1873

Economic crises carry with them hugely devastating results: high rates of unemployment and bankruptcy are emblematic of the more modern ones. Often, a crisis is not precipitated by a flaw in the overall economy but instead a dangerous practice in a sector of that economy. Perhaps that sector has companies or individuals who have undertaken a course of action that threatens the market, and perhaps no authority figure—governmental or otherwise—can curb or stop that dangerous behavior and prevent the damage from being done. By 1873, the American railroad industry had become an industry asking for a crisis: throughout the country—and increasingly in Europe—the American railroad companies had been a popular investment; the lure of high returns was too strong for investors to resist, and the tinderbox for the impending blaze would be the bonds of railroad companies. Those bonds were the sought after investment of the time and had been collateralized—just as a piece of real estate is collateralized for a mortgage—several times over (therefore inflating the value of the bonds, the volume of the railroad bond market, and the risk of the investments). Investors, through their greed, were guaranteeing that when the market did face a disruption—and it inevitably would—that disruption, that spark, would be the beginning of a years-long economic depression.

(more…) -

Crédit Mobilier

Americans’ trust in their government has always ebbed and flowed, and those ebbs and flows have largely depended on whether the government and its officers have acted in ways that earned the trust of its citizens or in ways that led the government to be mired in scandal—therefore sullying its reputation. Some of the largest ebbs in trust have come after officials in the top echelon of government—Senators, Representatives, Presidents and their cabinets—have used their offices for their own benefit. Two months before the election of 1872, news broke of a scandal that would extend well into 1873 and implicate politicians as prominent as the Vice President, and that scandal foreshadowed the ways in which big business and politics would intertwine in not only the Nineteenth Century but the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries.

(more…)