With the Civil War’s end, the United States had put itself back on course to become one of the leading economies in the world. Economic strength begets influence around the world, and America was no exception to this principle; it now was entering an era—an era that, as of the time of this writing, has not come to a close—of taking part in directing the world’s affairs. More than that, America now had the potential to reshape parts of the world in its image. After all, this was the 19th Century, and the era of empires was arguably at its peak—although its sun was setting. For the time, there was an expectation: if you had the opportunity and resources to expand, to take more land and more people into your orbit, you took full use of the opportunity. To abstain from this mode of operation was to concede a wealth of riches, and indulging in the taking of those riches was no cause for shame; every one of the major powers—some for decades, some for centuries—had carved up a part of the world, had made their own empire.

(more…)Tag: William Seward

-

The Second Father

In February 1861, Abraham Lincoln traveled to the Western Railroad Depot carrying his trunk tied with a rope and with the inscription, “A. Lincoln, White House, Washington, D.C.” Friends and family prepared him for the train ride from Illinois to Washington which would take twelve days and bring the President-elect into contact with tens of thousands of citizens. Lincoln had been “unusually grave and reflective” as he lamented “parting with this scene of joys and sorrows during the last thirty years and the large circle of old and faithful friends,” and when he went to his law partner for sixteen years, Billy Herndon, he assured him that his election to the presidency merely placed a hold on his partnership role: “If I live I’m coming back some time, and then we’ll go right on practising law as if nothing had ever happened.” As he stood on his private train car and addressed the crowd of well-wishers, the sentiment was no less heartfelt: “My friends—No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. . . . I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.” And so, with the crowd moved to tears, Lincoln would leave Springfield for the last time in his life with the train slowly moving “out of the sight of the silent gathering.” Within the train car, furnished with dark furniture, “crimson curtains, and a rich tapestry carpet,” Lincoln “sat alone and depressed” without his usual “hilarious good spirits.” (more…)

-

The Emancipation Proclamation

American history is replete with instances of the public pressuring a president to take action on an issue. On far fewer occasions, presidents, through speaking to voters, calling for congressional action, or issuing executive orders, have risked political capital to lead the public to advance on a prominent issue. In the middle of 1862, President Abraham Lincoln convened his Cabinet to discuss taking action on an issue that had been consuming him for weeks but was likely to endanger his bid for reelection in 1864 and was certain to change the direction of the ongoing and increasingly bloody Civil War. (more…)

-

The Outbreak of the Civil War

Within a matter of weeks of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency beginning, the gravest crisis of perhaps any president confronted him and the nation: civil war. (more…)

-

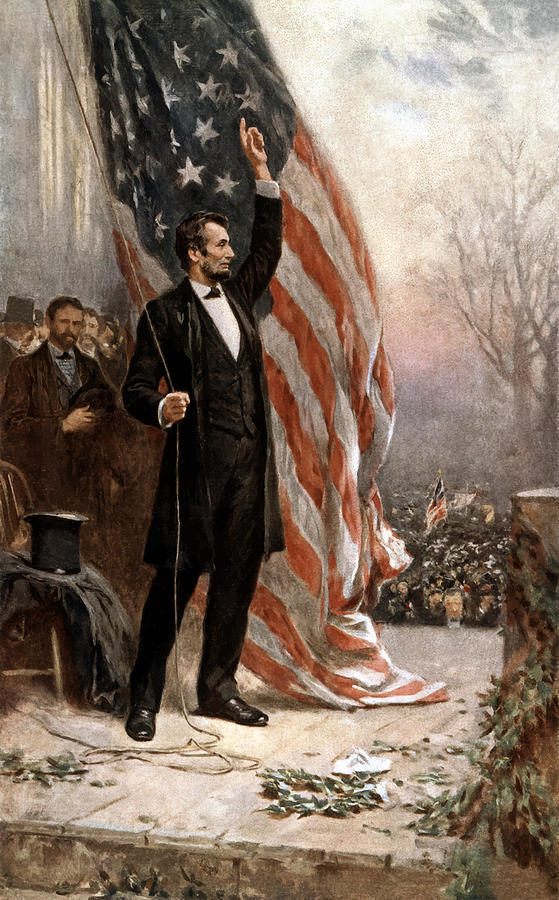

The Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

From the time of the Election of 1860 to the beginning of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, there was uncertainty as to how Lincoln and his administration would handle the growing Confederacy and existential crisis facing the country. (more…)

-

The North’s Attempt at Salvation

Aerial Perspective of Washington DC in 1861. The Deep South’s animating of a Second American Revolution, by seceding from the Union and laying the foundation for an operational Confederate government, forced the North to either suppress the South’s uprising or craft a resolution. The likelihood of war would deter any widespread northern suppression, leaving the question: What compromise could the North propose that appeased the South and put both sections of the country on a path of coexistence? While variations of this question had been posed in the years leading up to 1860, at no prior point were states seceding from the Union en masse to form a rival government. (more…)

-

The Secession of the Deep South

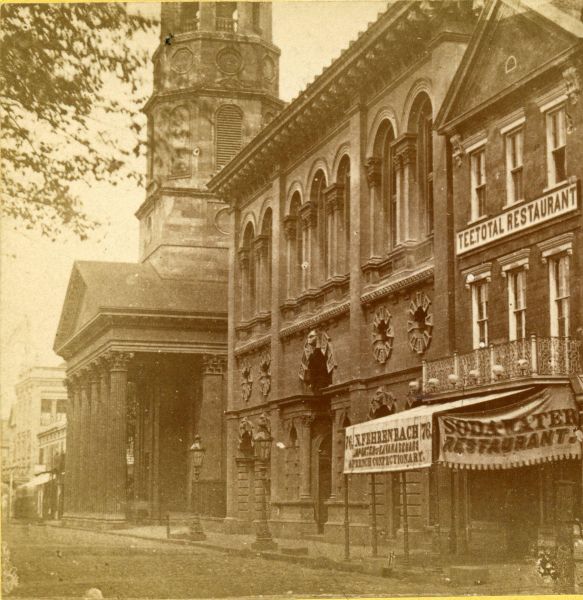

Secession Hall in Charleston, South Carolina. Credit: The Civil War Trust. In the wake of the disconcerting result of the Election of 1860, the nature of southern secessionism suggested the imminent secession of at least some southern states from the Union. The timing and execution of states actually seceding from the Union was unclear, but the Deep South was prepared to act first. (more…)

-

The Election of 1860

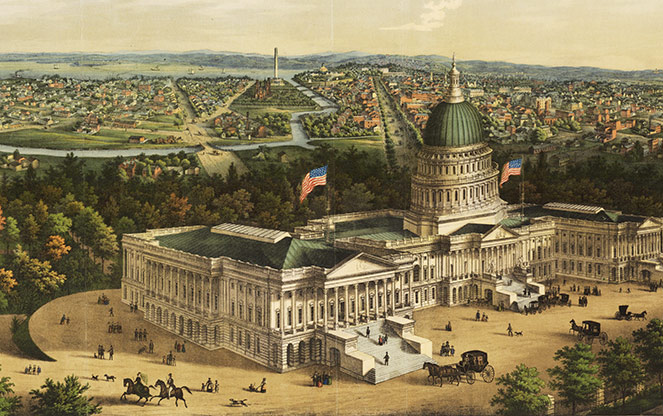

The United States Capitol in 1860. Courtesy: Library of Congress Every presidential election is consequential, but the Election of 1860 would play a significant role in whether the United States would remain one nation. The division of the North and South on the issue of slavery threatened to cause a secession of the South. The result of the election would determine whether that threat would materialize and cause a Second American Revolution. (more…)

-

The Evolving Political Parties of the 1850s

Panoramic View of Washington, DC in 1856. Courtesy: E. Sachse & Co. The Democratic Party and Whig Party were the dominant political parties from the early 1830s up until the mid-1850s. Both were institutions in national politics despite not having a coherent national organization by cobbling together a diverse group of states to win elections. While the Democrats had a more populist agenda, the Whigs were more focused on pursuing industrialization and development of the country. See David Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861, 226. While the Democratic Party would survive to the present day, the Whig Party would not survive the mid-1850s, not as a result of its own ineptness but because of the changing political landscape of that era. (more…)

-

Bleeding Kansas

Tallgrass Prairie, Kansas. After the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, William Seward proclaimed to the Senate that “[w]e will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers as it is in right.” Congressional Globe, 33 Cong., 1 sess., appendix, 769. Rather than settling the issue of slavery in Kansas, the Act made Kansas the figurative and literal battleground for the issue of slavery.